By Akshita Kulshreshstha

Abstract

Migration is a transformative force that reshapes societies, economies, and geographies. In India, internal migration—particularly from rural to urban areas—is driven by a complex interplay of push and pull factors. Push factors such as agrarian distress, unemployment, poverty, environmental degradation, and lack of basic services compel individuals to leave their native villages. Simultaneously, urban centers exert a magnetic pull through promises of better employment, education, healthcare, infrastructure, and social mobility. This essay explores the multifaceted nature of migration, analyzing its patterns, typologies, and temporal dimensions. It delves into the socio-economic and environmental drivers behind migration and examines its profound impacts on both urban and rural development. Urban areas benefit from labor influx and cultural diversity but face challenges like overcrowding, informal settlements, and strained infrastructure. Rural regions, while gaining remittances and returning skills, suffer from depopulation, gender imbalances, and economic stagnation. Through case studies and statistical insights, the essay emphasizes the need for balanced regional development, inclusive policy frameworks, and sustainable planning. Understanding migration not only reveals the aspirations and struggles of millions but also offers pathways to build resilient, equitable, and interconnected communities across India.

Introduction

Migration is the movement of people from one place to another, often from rural to urban areas in India. It is driven by a combination of push factors (forces that drive people away from rural areas) and pull factors (attractions of urban areas). It reflects deep socio-economic and environmental disparities. On the rural side, push factors act as forces of repulsion, compelling individuals and families to leave their native villages. Agricultural distress is a major contributor, with small landholdings, low productivity, and heavy dependence on unpredictable monsoons making farming unsustainable. The lack of non-agricultural employment opportunities leads to widespread unemployment and underemployment, leaving many without viable income sources. Poverty and indebtedness further exacerbate the situation, as families struggle to maintain basic livelihoods. Environmental stressors such as floods, droughts, soil erosion, and declining groundwater levels make rural life increasingly precarious. Social challenges, including caste-based discrimination and inadequate access to education and healthcare, limit upward mobility and quality of life. Additionally, conflict and displacement caused by insurgencies or land acquisition for infrastructure projects like dams and mining operations force many to migrate involuntarily.

In contrast, urban areas present a set of pull factors that attract migrants with the promise of a better future. Cities offer diverse employment opportunities in industries, construction, services, information technology, and transportation, often accompanied by higher wages and perceived improvements in living standards. Educational institutions such as colleges, universities, and coaching centers provide access to academic advancement. Urban healthcare facilities, markets, and communication networks offer modern services that are often unavailable in rural settings. The potential for social mobility, including escape from rigid caste and community structures, is another powerful motivator. Moreover, the availability of modern amenities—electricity, reliable transport, entertainment, and digital connectivity—makes urban life appear more desirable and progressive. Together, these factors create a powerful incentive for rural populations to migrate in search of opportunity, security, and a better quality of life.

According to the Census of India 2011 and various NSSO surveys, migration continues to be a significant demographic phenomenon in India, involving nearly 37% of the total population — approximately 450 million people. Migration in the country largely occurs within rural areas, with rural-to-rural movements accounting for about 55% of all migration. This is followed by rural-to-urban migration (around 22%), reflecting the steady pull of cities as centers of economic opportunity, while urban-to-urban and urban-to-rural movements make up smaller proportions. The pattern of migration also shows a clear gender divide. Women migrate predominantly for social reasons, particularly marriage, which constitutes nearly 70% of female migration. In contrast, men are more likely to migrate for economic purposes such as employment, business, or seeking better livelihood opportunities.

At the state level, certain regions act as major sources and destinations of migration. States like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Rajasthan experience high rates of out-migration due to limited local employment opportunities and agrarian distress. On the other hand, economically advanced states and urban centers such as Delhi, Maharashtra (notably Mumbai and Pune), Gujarat (particularly Surat and Ahmedabad), and Karnataka (Bengaluru) attract large numbers of migrants seeking jobs and improved living conditions. In recent years, there has also been an emerging trend of inter-state and international migration among skilled professionals, especially in sectors like information technology, healthcare, and education. This shift reflects the growing mobility of India’s educated workforce and the increasing role of migration in shaping both the country’s urbanization patterns and its labor market dynamics.

Migration has far-reaching impacts on both urban and rural regions in India, influencing economic growth, social structures, and patterns of development. In urban areas, migration contributes significantly to economic expansion by providing a steady supply of affordable labor essential for industries, construction, transportation, and domestic services. Migrants play a vital role in driving urban productivity and fostering cultural diversity, as they bring with them new traditions, cuisines, and ideas that enrich the social fabric of cities. However, this rapid inflow of people also creates serious challenges. Overcrowding in major cities leads to housing shortages and the proliferation of slums and informal settlements, such as Dharavi in Mumbai. The growing population puts immense pressure on urban infrastructure, including water supply, sanitation, transportation, and healthcare facilities. Additionally, limited job opportunities result in high levels of informal employment, while competition for resources can sometimes lead to social tensions or conflicts between migrants and local residents.

At the same time, migration profoundly affects rural areas, which are often the source regions. The outflow of migrants generates significant economic benefits through remittances, which improve household income, housing quality, healthcare access, and educational opportunities. These remittances often stimulate local economies and help reduce poverty. Moreover, return migrants contribute to rural development by bringing back valuable skills, ideas, and technologies acquired in cities or abroad. Migration also helps ease demographic pressure on limited agricultural land. Nevertheless, there are also several negative consequences. The departure of young and skilled workers can lead to a “brain drain,” leaving behind an aging population and creating a gender imbalance, as male out-migration results in the feminization of agriculture, with women taking on more agricultural and household responsibilities. Over time, this can weaken traditional social ties and cultural practices, leading to a decline in community cohesion. Furthermore, an overdependence on remittances can make rural households economically vulnerable if migrants face job losses or crises in destination areas.

Overall, migration serves as both a driver and a challenge to India’s development. While it stimulates economic growth, promotes cultural exchange, and supports rural livelihoods, it also highlights the urgent need for balanced regional development, better urban planning, and policies that ensure both source and destination regions benefit equitably from the movement of people.

Migration, urbanization, and development in India are closely interconnected, forming a dynamic and interdependent nexus that shapes the country’s social and economic transformation. Migration is one of the primary forces driving urbanization, as millions of people move from rural to urban areas in search of better employment opportunities, education, healthcare, and improved living standards. This continuous flow of people fuels the expansion of cities, stimulates economic activity, and contributes to the diversification of urban economies. At the same time, migration reinforces the rural–urban continuum, highlighting the deep interdependence between villages and cities. Rural areas rely on urban centers for access to markets, employment opportunities, modern services, and remittances sent by migrants that sustain rural livelihoods. Conversely, cities depend on rural regions for essential resources such as food, labor, raw materials, and the cultural diversity that migrants bring with them.

However, this relationship also presents significant challenges. The uneven pace of development between rural and urban areas often leads to distress migration, where people are compelled to leave their villages due to poverty, unemployment, and lack of basic amenities. This type of migration can strain urban infrastructure and contribute to the growth of informal settlements, while leaving rural areas depopulated and economically weaker. To address these issues, India needs balanced regional development policies that create livelihood opportunities and improve infrastructure in rural regions while ensuring sustainable urban growth. Strengthening small and medium towns, improving rural industries, and enhancing connectivity between villages and cities can help reduce migration pressures and promote more equitable development. Ultimately, managing this migration–urbanization–development nexus effectively is key to achieving inclusive, sustainable, and regionally balanced growth in India.

Discussion

Push and Pull Factors Shaping Internal Migration Patterns in India : Internal migration—the movement of people within national borders—represents one of the most significant demographic processes shaping India’s social and economic landscape. Push and pull factors create complex migration patterns that transform both rural and urban areas. These factors don’t operate in isolation but form an interconnected web of influences that motivate millions of Indians to relocate annually in search of better opportunities or to escape challenging conditions. By examining these dynamics, we gain crucial insights into how population movements reflect and respond to broader socioeconomic inequalities across regions.

Push factors are negative circumstances that compel people to leave their places of origin. In India’s rural contexts, several significant push factors contribute to the steady flow of migration toward urban centers. Economic distress and the lack of sustainable livelihood opportunities remain among the most significant push factors driving migration from rural India. Agriculture, which continues to employ a large share of the rural population, is no longer able to provide a stable and sufficient source of income for many households. One major issue is agricultural underemployment — the seasonal nature of farming means that many rural workers have jobs only during specific periods of the year, leaving them underutilized or jobless for months. Additionally, land fragmentation caused by generations of property division has resulted in increasingly smaller plots of land that are often economically unviable to cultivate. This limits productivity and reduces the potential for agricultural profitability. Moreover, income instability has become a persistent problem, as farmers remain highly dependent on uncertain factors such as rainfall, fluctuating crop prices, and rising input costs for seeds, fertilizers, and irrigation. These vulnerabilities make rural livelihoods precarious and push many to seek alternative means of survival in urban areas.

The story of Rajesh, a small farmer from Bihar who owned just one acre of land, reflects the lived reality of countless rural households. After suffering consecutive poor harvests and struggling to feed his family of five, Rajesh made the difficult decision to migrate to Delhi in search of work. His journey underscores a harsh truth—migration in such contexts is not a matter of choice or ambition but a compulsion born out of necessity. For many like Rajesh, leaving their villages behind becomes the only viable way to cope with persistent rural distress and pursue a more secure livelihood, even if it means facing uncertainty and hardship in the city.

In addition to economic hardship, inadequate infrastructure and poor access to essential services serve as major push factors driving migration from rural to urban areas in India. Many rural regions continue to suffer from significant gaps in healthcare, education, and basic amenities, creating an environment where sustaining a decent quality of life becomes increasingly difficult. Healthcare disparities are particularly stark — rural residents often face limited access to hospitals, doctors, and medicines, forcing them to travel long distances to urban centers for even basic treatment. This lack of timely medical care not only endangers lives but also places additional financial and emotional strain on families. Similarly, educational deficiencies are widespread, as many villages lack quality schools, trained teachers, and higher education institutions. Parents aspiring for better futures for their children often see migration as the only option to access better educational opportunities in towns and cities.

The gap in basic amenities further exacerbates the situation. Irregular electricity supply, inadequate drinking water systems, poor sanitation, and unreliable transportation infrastructure collectively diminish the standard of living in rural areas. These deficits make urban life, despite its challenges, appear more attractive and promising. The disparity is particularly evident in regions such as eastern Uttar Pradesh, where access to healthcare facilities is reported to be up to five times lower than in the state’s urban centers. For families in such areas, migration is not merely a pursuit of prosperity but often a response to pressing needs for survival, health, and dignity. This stark contrast between rural deprivation and urban opportunity continues to be a powerful force shaping India’s migration patterns and urban growth.

Environmental factors and natural disasters have become increasingly important drivers of internal migration in India, intertwining with economic and social challenges to shape movement patterns across the country. Climate change is a major catalyst, as shifting rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, and frequent extreme weather events disrupt traditional agricultural practices and make farming increasingly unpredictable. These environmental changes directly threaten the livelihoods of millions who depend on agriculture, livestock, and natural resources for survival. Natural disasters such as floods, droughts, and cyclones can devastate entire communities in a matter of days, destroying homes, crops, and infrastructure, and forcing people to relocate—sometimes permanently. Additionally, resource depletion, including declining groundwater levels, soil degradation, and deforestation, has further eroded the sustainability of rural economies, leaving communities with fewer means to sustain themselves locally.

The consequences of these pressures are clearly visible in various parts of India. In the coastal regions of Odisha and West Bengal, recurring cyclones such as Fani and Amphan have created a steady flow of environmental migrants moving inland in search of safety and stability. Similarly, in Maharashtra’s drought-prone districts, prolonged water scarcity and failed monsoons have compelled thousands of families to abandon their ancestral homes and migrate to more water-secure urban and semi-urban areas. These patterns underscore how environmental degradation and natural disasters not only displace populations but also accelerate broader social and economic transformations, intensifying rural–urban migration trends across India.

At the same time, the pull factors associated with migration play a critical role in shaping these movements. Urban centers offer a promise of greater livelihood opportunities, better wages, improved access to healthcare and education, and more reliable infrastructure. For many rural families facing environmental uncertainty, cities symbolize stability and the hope of rebuilding their lives. Thus, while environmental stress acts as a push factor, the perceived economic and social advantages of urban areas serve as powerful pull factors, collectively driving the ongoing migration flows within India.

While push factors drive people away from rural areas, pull factors actively attract them to specific destinations, particularly urban centers. These positive forces create magnetic appeal for potential migrants.

The pursuit of better economic opportunities and employment prospects remains the most powerful pull factor driving migration from rural to urban areas in India. Cities are widely perceived as spaces of economic advancement, offering individuals and families the possibility of improving their living standards and achieving upward mobility. One of the main attractions is the higher wage potential — urban jobs often pay two to three times more than comparable work in rural areas, providing a significant financial incentive for migration. Moreover, urban economies are characterized by job diversity, offering a broad range of employment opportunities across both formal and informal sectors. From industrial and construction work to services, retail, and domestic labor, cities can accommodate workers with varying levels of education and skill. In contrast to the uncertainties of agricultural livelihoods, non-agricultural employment in urban areas often provides more stable and predictable income, which helps families plan for the future and invest in health, housing, and education.

This trend is particularly visible in India’s rapidly expanding metropolitan regions. The construction boom in cities such as Bengaluru, Mumbai, and Gurgaon has generated massive demand for labor, attracting thousands of migrants each year. Similarly, the manufacturing hubs of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu draw workers from economically weaker states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Odisha, where limited job options and agricultural distress push people to seek work elsewhere. Even within the informal sector — including street vending, domestic work, and small-scale services — urban employment often ensures a more consistent source of income than rain-dependent farming in drought-prone rural regions. Thus, the economic pull of cities continues to act as a powerful magnet, shaping migration flows and reinforcing India’s ongoing urbanization and socio-economic transformation.

Another significant pull factor driving migration toward urban areas in India is the superior availability of infrastructure and public services that greatly enhance the quality of life. Cities generally provide far better access to essential services compared to rural regions, making them attractive destinations for individuals and families seeking improved living conditions. Healthcare access is one of the most notable advantages — urban centers are home to a higher concentration of hospitals, clinics, and medical specialists, ensuring timely and advanced healthcare that rural populations often lack. This is particularly crucial for families dealing with chronic or serious health conditions, who may choose to migrate specifically to access specialized treatment.

Urban areas also offer educational opportunities that are far superior to those available in most rural districts. Quality schools, colleges, technical institutes, and universities are concentrated in metropolitan regions, attracting ambitious students from smaller towns and villages who aspire to pursue higher education and professional careers. Furthermore, transportation networks in cities — including buses, metros, and railways — make mobility easier and more affordable, enabling people to access employment, education, and healthcare efficiently. In addition, urban centers provide better utilities and housing infrastructure, with more reliable electricity, piped water supply, and diverse housing options ranging from affordable rentals to formal housing societies.

For many rural households, the contrast between inadequate rural infrastructure and the relative convenience of urban living serves as a decisive factor in migration. Cities symbolize progress, connectivity, and opportunity — not only as centers of employment but also as spaces offering access to the basic services and facilities necessary for a dignified and modern life. This superior urban infrastructure continues to attract migrants from across the country, reinforcing the steady growth and expansion of India’s cities.

Beyond economic and infrastructural advantages, social and cultural attractions play a significant role in drawing people toward cities in India. Urban areas often represent spaces of freedom, diversity, and opportunity — qualities that strongly appeal to individuals, especially the youth, from conservative or traditional rural settings. One of the most compelling aspects of city life is the greater personal freedom it offers. Unlike rural communities, where social norms and expectations can be rigid and community surveillance intense, cities tend to have more liberal and individualistic environments. This relative anonymity allows people to express themselves more freely, pursue varied lifestyles, and make independent choices regarding education, career, and relationships.

Cities also provide access to rich cultural and recreational opportunities that enhance quality of life. The presence of theatres, art galleries, music festivals, sports venues, restaurants, and diverse entertainment options creates a vibrant social atmosphere unavailable in most rural areas. Moreover, expanded social networks in cities allow people to connect with individuals from different regions, languages, and backgrounds, fostering broader perspectives and sometimes enhancing social mobility and professional opportunities. This exposure to diversity often becomes an enriching experience, encouraging personal growth and cultural exchange.

For many young adults from conservative rural communities, the cultural vibrancy and openness of cities like Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata hold immense appeal. These urban centers symbolize modernity, creativity, and change — offering an escape from the monotony or restrictions of rural life. As a result, migration is not only an economic or survival strategy but also a quest for identity, freedom, and a more fulfilling social existence in an increasingly urbanized India.

Internal migration in India defies simple categorization, manifesting in various forms that reflect the complexity of migrants’ circumstances and motivations.

Migration in India can be categorized into different typologies based on the motivations driving individuals to move, highlighting the diversity of migration experiences and the underlying socio-economic factors. Survival migration occurs when people are compelled to relocate due to immediate threats to life or livelihood, such as natural disasters, floods, droughts, or acute economic distress. In these cases, migration is often urgent and unplanned, leaving individuals and families with few resources or alternatives. Subsistence migration, on the other hand, takes place when origin locations can no longer provide the minimum requirements necessary to maintain basic living standards, such as food, shelter, or employment, forcing households to seek sustenance elsewhere.

Sponsored migration refers to movements facilitated by existing networks of earlier migrants, who provide crucial support such as information about opportunities, temporary accommodation, and employment connections. These networks reduce the risks associated with migration and make the transition to a new location smoother. Finally, voluntary migration is driven primarily by choice rather than necessity, as individuals or families move to pursue better educational, professional, or lifestyle opportunities. The contrast between these typologies is evident in real-life examples: a farmer from drought-affected Marathwada represents survival migration, compelled to leave his village to secure basic survival, whereas an educated professional relocating from a small town to Hyderabad’s thriving tech sector exemplifies voluntary migration, motivated by career advancement and improved living standards. While both are internal migrants, their experiences, available resources, challenges, and long-term trajectories differ dramatically, illustrating the complex and multifaceted nature of migration in India.

The temporal dimensions of migration add another layer of complexity to understanding population movements in India, as the duration and pattern of relocation vary widely across different groups. Seasonal migration is a temporary movement closely tied to agricultural or industrial cycles, where individuals travel for work during specific periods and return to their place of origin afterward. This type of migration is particularly prevalent in sectors such as construction and agriculture, with an estimated 100 million seasonal migrants moving across India each year. For instance, construction workers from Odisha often travel to Kerala during the dry season to take advantage of employment opportunities, returning home during the monsoon months to engage in farming or attend to family responsibilities.

Circular migration involves repeated movement between source and destination areas, often over several years, without the intention of permanent relocation. Migrants in this category maintain strong ties with their place of origin while continuously participating in labor markets elsewhere. In contrast, permanent migration entails a one-way relocation with the explicit goal of establishing a new residence, often accompanied by long-term social, economic, and cultural integration into the destination region. Another pattern, step migration, describes gradual movement through a series of locations, typically progressing from smaller towns or villages to larger urban centers, often in search of better opportunities and improved living conditions. These temporal patterns illustrate that migration in India is not a uniform process but rather a dynamic spectrum of movements shaped by economic cycles, social networks, and individual aspirations, each with distinct implications for both origin and destination regions.

The temporal dimensions of migration introduce an important perspective on population movement in India, highlighting how the duration and recurrence of relocation influence both migrants’ lives and the regions they connect. Seasonal migration represents a widespread and largely cyclical pattern, closely tied to agricultural or industrial work schedules. Individuals engage in temporary relocation during periods of peak labor demand, returning to their home villages once the season ends. This pattern is particularly common in construction, agriculture, and allied sectors, with estimates suggesting that nearly 100 million seasonal migrants move within India annually. A clear example is construction workers from Odisha who travel to Kerala during the dry season for employment and return home during the monsoon to participate in farming or manage family obligations. Such movements allow households to supplement income without permanently leaving their community, but they also reflect the vulnerability of workers to irregular employment and economic precarity.

Circular migration extends this concept by involving repeated movement over years, with migrants maintaining ongoing economic and social ties to their places of origin while continually seeking employment in destination areas. In contrast, permanent migration represents a one-way relocation, often motivated by long-term economic, educational, or social goals, requiring migrants to integrate into new communities, adapt to urban lifestyles, and establish stable livelihoods. Step migration illustrates a more gradual process, where individuals move through a hierarchy of settlements — from small villages to towns, and eventually to large cities — leveraging each step to access better opportunities and gradually improve their socio-economic position. Collectively, these temporal patterns underscore that migration in India is far from homogeneous; it is a dynamic and multi-layered phenomenon shaped by economic cycles, environmental pressures, social networks, and personal aspirations. Understanding these temporal dimensions is crucial for designing policies that address both the opportunities and vulnerabilities associated with migration, ensuring that the benefits are shared equitably between origin and destination regions.

Internal migration in India produces a complex balance of impacts that extend across economic, social, cultural, and infrastructural dimensions, affecting both the regions migrants leave and those they move to. At the origin, migration often alleviates labor pressure and provides households with financial lifelines through remittances, which are frequently invested in education, healthcare, housing, and small-scale businesses. These inflows can stimulate local economies and improve living standards for families remaining in rural areas. However, the departure of productive and skilled workers can also create challenges, such as reduced agricultural output, “brain drain,” and the feminization of rural labor, which may increase the burden on women and compromise long-term rural development.

In destination regions, migrants contribute significantly to economic growth by supplying labor across formal and informal sectors, fostering urban dynamism, and enriching cultural diversity. Their presence facilitates the exchange of ideas, traditions, and skills, strengthening social networks and promoting innovation. At the same time, rapid in-migration can strain urban infrastructure, housing, and public services, leading to overcrowding, the proliferation of informal settlements, and increased demand on healthcare, education, and transportation systems. Social tensions may also arise between migrant and local populations, challenging urban cohesion and governance.

Overall, internal migration generates both opportunities and vulnerabilities, creating a complex interplay of benefits and costs. While it supports economic growth, cultural exchange, and household resilience, it also exposes gaps in infrastructure, governance, and social protection. Understanding these multifaceted impacts is essential for policymakers to design strategies that maximize the positive contributions of migration while mitigating its adverse consequences, ensuring that both sending and receiving regions can thrive in a sustainable and inclusive manner.

The economic impacts of internal migration in India are wide-ranging and extend far beyond the individual migrants themselves, influencing both sending and receiving regions. One of the most significant contributions is remittances, with migrants estimated to send around ₹1.5 trillion annually to rural households, providing a crucial source of income that supports basic needs, education, healthcare, and housing improvements. These remittances often act as a catalyst for local economic development, enabling families to invest in human capital and improve their standard of living. Migration also affects labor markets by alleviating surpluses in rural areas, where underemployment and seasonal work are common, while simultaneously meeting the high demand for labor in urban centers, particularly in construction, manufacturing, services, and informal sectors. This redistribution of labor can enhance overall economic efficiency and productivity at a regional and national level.

However, migration also has potential downsides for rural economies. The outflow of productive workers, particularly young and skilled individuals, can reduce agricultural output, slow local development, and create gaps in essential services. Over time, this concentration of human capital in urban areas can exacerbate regional inequalities, as already-developed regions continue to attract resources and talent while rural areas lag behind. Despite these challenges, studies consistently show that households receiving remittances are more likely to invest in education, healthcare, and housing compared to non-migrant households, highlighting migration’s role as both a survival strategy and an economic development mechanism. In essence, migration functions as a double-edged economic force—simultaneously alleviating rural pressures, fueling urban growth, and shaping regional disparities.

Internal migration in India has profound social and cultural impacts, reshaping the dynamics of both sending and receiving communities. In many rural areas, migration is predominantly male-driven, leaving behind households headed by women. This shift often reshapes gender roles and responsibilities, with women taking on greater authority in decision-making, household management, and financial planning. For example, studies in Kerala have shown that women in families with migrant men increasingly manage family resources, make key household decisions, and oversee agricultural or small-scale economic activities, highlighting the empowerment potential embedded in migration.

Migration also facilitates cultural exchange, as individuals bring ideas, traditions, practices, and innovations from their home regions to urban centers, contributing to the social diversity and vibrancy of cities. Migrant communities often form cultural enclaves in destination areas, such as Mumbai or Delhi, preserving regional languages, festivals, cuisine, and social networks while simultaneously integrating into the broader urban fabric. However, rapid in-migration can create social cohesion challenges, particularly in cities where resources are scarce or competition for jobs and housing is intense. In some cases, this can lead to nativist sentiments or tensions between local residents and migrant populations. Overall, migration acts as both a driver of cultural enrichment and social transformation, reshaping family structures, expanding social networks, and contributing to the evolving mosaic of India’s urban and rural societies.

Large-scale internal migration in India places significant infrastructural and service provision pressures on destination areas, particularly rapidly growing cities. One of the most visible consequences is housing strain, as the influx of migrants often outpaces the development of formal residential infrastructure. This has led to the expansion of informal settlements and slums, where living conditions are overcrowded, unsafe, and lacking basic amenities. For instance, nearly half of Mumbai’s population resides in such informal settlements, reflecting the city’s inability to keep pace with the demand generated by in-migration.

In addition to housing, public services such as healthcare, education, and transportation are frequently overburdened. Urban hospitals and clinics struggle to provide timely care, schools face overcrowding, and public transit systems are stretched beyond capacity, reducing accessibility and efficiency for both migrants and long-term residents. Rapid population growth also complicates urban planning and sustainable development, as cities struggle to expand infrastructure, manage waste, and provide reliable water and electricity systems. Delhi’s water supply network, originally designed for a much smaller population, is now under significant stress due to millions of migrants settling in the National Capital Region over recent decades. These challenges highlight the urgent need for proactive urban planning, inclusive housing policies, and scalable service delivery mechanisms to ensure that cities can accommodate migration sustainably while maintaining quality of life for all residents.

Effective migration policy in India requires a balanced approach that recognizes migration as an inevitable aspect of economic and social development while striving to maximize its benefits and minimize associated costs. One key strategy involves origin-focused interventions that address the push factors compelling people to leave their home regions. Strengthening rural economies through agricultural modernization, rural industrialization, and the promotion of non-farm livelihoods can create sustainable employment opportunities locally, reducing the necessity for migration driven by economic distress. Similarly, service equalization—improving access to quality healthcare, education, and basic infrastructure in rural areas—can help narrow the gap between urban and rural living standards, making remaining in the village a viable option for families. Addressing environmental vulnerabilities is also critical; climate resilience initiatives such as water management, soil conservation, and disaster preparedness can mitigate environment-driven migration caused by floods, droughts, or resource depletion. Programs like the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) provide minimum employment guarantees in rural areas, directly reducing distress migration by offering a stable source of income. Complementary efforts to establish educational and healthcare hubs in rural regions further help prevent service-seeking migration, enabling households to access essential services without relocating to urban centers. Collectively, these origin-focused policies aim to create conditions where migration becomes a choice rather than a necessity, empowering communities while easing pressure on cities.

Given the inevitability of migration, destination-focused approaches are essential to ensure that urban areas can accommodate incoming populations sustainably while maximizing their contributions to local development. One key strategy is inclusive urban planning, which incorporates migration projections into infrastructure development, public services, and transportation systems to anticipate demand and prevent congestion. Housing policy is equally important, with cities needing to develop affordable and safe residential options to prevent the proliferation of informal settlements and slums. Integration programs further support migrants by facilitating access to social protection, education, healthcare, and other essential services, helping them establish stable lives and contribute effectively to the urban economy.

Some cities in India have already implemented innovative strategies in this regard. For example, Surat in Gujarat has embraced migrant-inclusive urban planning, recognizing that in-migration fuels local economic growth and contributes to the city’s dynamism. Similarly, several states are piloting mobile ration card systems, which allow migrants to access food subsidies and social welfare benefits regardless of their current location, addressing one of the major barriers to migrant welfare. By combining proactive planning, affordable housing initiatives, and targeted integration measures, destination-focused policies aim to transform migration from a source of urban strain into an opportunity for sustainable economic growth, social inclusion, and improved quality of life for both migrants and long-term residents.

A rights-based approach to migration is essential for improving outcomes for migrants and ensuring that their movement contributes positively to both origin and destination communities. Central to this approach is the protection of labor rights, guaranteeing that migrant workers receive equal treatment, fair wages, safe working conditions, and access to social security benefits. Equally important is the development of portable social protection systems, which allow benefits such as food subsidies, pensions, and healthcare entitlements to follow migrants across state and district boundaries, reducing the vulnerability associated with relocation. Initiatives like the One Nation, One Ration Card scheme represent significant progress in this area, enabling migrants to access subsidized food regardless of where they settle in India.

Beyond economic and social protections, political representation is a critical component of a rights-based framework. Mechanisms that allow migrants to participate in local governance and decision-making processes in both their origin and destination communities can strengthen inclusion, accountability, and social cohesion. Despite these advancements, significant gaps remain in ensuring migrants’ full access to healthcare, education, housing, and political participation, particularly for those in informal employment or unplanned settlements. Addressing these gaps requires coordinated policy action across multiple levels of government, reinforced by legal protections and institutional support. By embedding migration policies within a rights-based framework, India can not only safeguard the dignity and well-being of migrants but also harness their potential as active contributors to regional development and social progress.

Internal migration in India functions as both a response to structural inequalities and a powerful mechanism for social and economic transformation. The push factors—such as limited livelihood opportunities, inadequate infrastructure, environmental pressures, and social constraints—drive people away from rural areas, while urban centers attract migrants with better employment prospects, services, and cultural opportunities. These movements not only reflect existing disparities but also actively reshape them, concentrating human capital, labor, and consumption in cities while leaving rural areas with evolving demographic and social structures. Recognizing the complex interplay of causes and consequences is critical for designing policies that maximize the benefits of migration, such as economic growth, cultural exchange, and human capital development, while minimizing its challenges, including urban congestion, service strain, and social inequality.

Looking ahead, technology is likely to profoundly influence internal migration patterns. The expansion of remote work, digital education platforms, and e-governance can allow individuals to access urban-quality opportunities without physically relocating, potentially reducing distress-driven rural-to-urban migration. Improved rural connectivity—through broadband, transportation, and financial inclusion—may encourage hybrid or circular migration models, where migrants can maintain ties to their origin communities while participating in urban labor markets. Despite these innovations, the traditional rural-to-urban migration pathway is likely to remain dominant for many sectors that require physical presence, such as construction, manufacturing, and informal services. What may emerge, however, are more diversified migration patterns, including town-to-town, rural-to-rural, and stepwise migrations facilitated by technology, which allow households to optimize economic and social outcomes. Ultimately, technology offers the potential to make migration less a necessity and more a strategic choice, enabling individuals to pursue better livelihoods while contributing to balanced regional development and reducing pressure on overburdened urban centers.

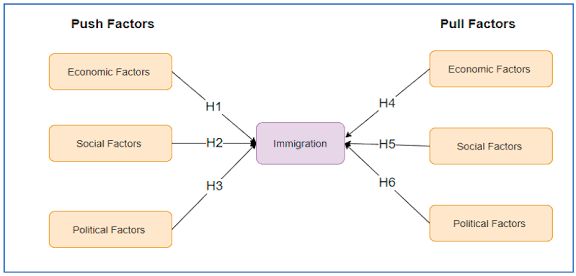

Push and Pull Factors Shaping External Migration Patterns in India: Immigration has long been a defining force in shaping societies, economies, and cultures across the world. The phenomenon is driven by a complex interplay of push and pull factors that influence individuals and families to relocate from one region or country to another. Understanding these dynamics provides critical insight into how migration reshapes demographic structures, influences urban and rural development, and drives socio-economic transformation over time. Push factors refer to the unfavorable conditions in a person’s home country that compel them to leave. Among the most significant are war, conflict, famine, and food insecurity. Armed conflicts displace millions, forcing individuals to flee in search of safety, political stability, and basic human security. Similarly, famine and food shortages drive large-scale migrations as people escape regions where survival becomes difficult. Economic hardship also plays a central role—limited job opportunities, poverty, and unemployment push individuals to seek better prospects abroad. Political instability, persecution, and discrimination based on religion, ethnicity, or ideology further contribute to migration, as people leave their homelands to find freedom, security, and acceptance elsewhere. Environmental disasters such as droughts, floods, or earthquakes also serve as major push factors, especially when they disrupt livelihoods and make entire regions uninhabitable.

On the other hand, pull factors are the favorable conditions that attract migrants to new destinations. Economic opportunities stand as one of the most powerful motivators—higher wages, job security, and career growth encourage people to move to regions with stronger economies. Educational prospects also play a crucial role, particularly for families seeking better futures for their children. Access to quality institutions, advanced programs, and global exposure makes education a major draw for migration. Family reunification policies further encourage movement, as individuals seek to join relatives who have already settled abroad, creating established networks that ease integration. Moreover, the promise of a better quality of life—including access to healthcare, safety, social services, and personal freedom—motivates countless migrants to relocate. These pull factors collectively shape the demographic and cultural landscape of destination countries, influencing their economies and social dynamics.

Immigration has historically transformed urban areas, each era leaving its unique mark. In the early 1900s, massive waves of European immigrants arrived in major cities like New York and Chicago, contributing to industrial growth and the creation of vibrant cultural enclaves. The 1950s saw post-war economic expansion, offering abundant job opportunities that attracted immigrants and supported rapid urbanization. By the 1980s, growing immigration increased housing demand, straining urban infrastructure and affordability while enhancing cultural diversity. In the 2020s, ongoing immigration continues to reshape city demographics—introducing new ideas, cuisines, and traditions, but also creating challenges such as overcrowding and pressure on social services. Despite these issues, urban areas benefit significantly from immigration through economic growth, innovation, and a dynamic multicultural environment.

While cities are often the primary destinations for immigrants, rural areas also experience notable impacts. Immigration can revitalize declining rural communities by introducing new labor forces and boosting agricultural productivity. Migrants contribute to sustaining local economies, filling essential labor gaps, and preventing population decline in aging regions. Rural areas often offer more affordable living conditions, which can attract both immigrants and return migrants seeking stability and open space. However, challenges remain, including the integration of newcomers into small, close-knit communities and the provision of adequate services to support growing populations.

Throughout history, immigration has evolved in response to global economic and political shifts. During the 19th century, massive European immigration to the United States spurred urban expansion and industrial growth. The early 20th century witnessed the Great Migration, where millions of African Americans moved from rural Southern states to Northern industrial cities, reshaping urban demographics and cultural identity. In the post–World War II era, economic reconstruction efforts across Europe and North America attracted waves of immigrants seeking employment and stability, leading to both urban diversification and rural rejuvenation. In the 21st century, immigration has become more globalized, involving refugees fleeing conflict zones, skilled professionals seeking opportunities in advanced economies, and migrants revitalizing rural regions facing depopulation.

The dynamics of immigration reveal how deeply interconnected economic, political, and social factors shape the movement of people. Both push and pull forces continue to influence migration patterns, driving change in urban growth, rural revitalization, and global cultural exchange. Understanding these dynamics is essential for policymakers, planners, and communities alike to harness immigration’s transformative potential while addressing its challenges. Ultimately, migration is not just a story of movement—it is a story of resilience, adaptation, and human aspiration for a better life.

Conclusion

Migration in India is a deeply embedded socio-economic phenomenon that reflects both the aspirations and adversities of its people. It is not merely a movement from one place to another, but a response to structural inequalities, environmental vulnerabilities, and the pursuit of dignity and opportunity. The push factors—ranging from economic hardship and environmental stress to social exclusion—highlight the urgent need for rural revitalization and inclusive growth. Conversely, the pull of urban centers underscores the importance of equitable access to services, infrastructure, and employment.

The impacts of migration are far-reaching. Urban areas thrive on the labor and cultural contributions of migrants, yet grapple with challenges like housing shortages, informal employment, and social tensions. Rural regions benefit from remittances and returning knowledge, but face demographic decline, feminization of agriculture, and erosion of traditional social structures. These dualities demand a holistic policy approach that bridges the rural–urban divide.

To manage migration effectively, India must invest in sustainable urban planning, strengthen rural economies, and enhance connectivity between regions. Policies should support small and medium towns, promote rural entrepreneurship, and ensure that migrants have access to rights, services, and social protection. Migration should be recognized not as a problem to be solved, but as a dynamic process that, if guided wisely, can drive national development, foster innovation, and build inclusive societies.

Ultimately, the migration–urbanization–development nexus is central to India’s future. By addressing the root causes of migration and leveraging its potential, India can create a more balanced, resilient, and humane developmental trajectory—one that honors the journeys of its people and builds bridges between its villages and cities.

References

Here are 15 authoritative and relevant sources that support and expand upon the themes discussed in your essay on migration trends and their impact on urban and rural development in India:

🔗 Reference Links

- Migration in India: Patterns, Causes & Impacts – Next IAS

- Push-Pull Factors for Migration in India – Home Science Journal

- Factors Affecting Migration in India: A Sociological Analysis – IJHSSM

- Census of India 2011 – Migration Tables

- NSSO Migration Survey Reports – Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation

- Urbanization and Migration in India – World Bank

- Internal Migration in India – UNESCAP

- Environmental Migration in India – IDMC

- India’s Urban Challenges – NITI Aayog

- Remittances and Rural Development – RBI Bulletin

- Labour Migration in India – ILO

- Migration and Development – OECD

- Climate Change and Migration – IPCC India Chapter

- Urban Slums and Informal Settlements – UN-Habitat India

- India’s Smart Cities Mission – Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs

You must be logged in to post a comment.