Decision-making in development and environmental policy often involves trade-offs between economic growth, ecological preservation, and social welfare. To systematically evaluate these trade-offs, economists and planners use Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA). CBA is a decision-support tool that compares the expected costs of a project or policy with its anticipated benefits, expressed in monetary terms, to determine whether it yields a net gain for society.

In environmental management, CBA helps policymakers evaluate whether activities such as dam construction, forest conservation, pollution control, or renewable energy projects create more benefits than costs when environmental and social impacts are considered.

Concept of Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) is a systematic approach to evaluating the economic efficiency of projects or policies. It measures all the costs (expenditures, damages, or losses) and benefits (gains, savings, or avoided damages) associated with an action, discounted over time to reflect present value.

The general principle is:

- If Benefits > Costs, the project is considered economically viable.

- If Costs > Benefits, the project may be reconsidered, redesigned, or rejected.

Key Features of CBA

- Monetization of Impacts: Both tangible and intangible impacts are expressed in monetary terms to enable comparison.

- Time Dimension: Costs and benefits occurring in the future are discounted to present values using a discount rate.

- Social Perspective: Unlike financial analysis (focused on profit for investors), CBA evaluates the broader impact on society, including externalities.

- Decision Rule: A project is accepted if the Net Present Value (NPV = Benefits – Costs) is positive or if the Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR) exceeds 1.

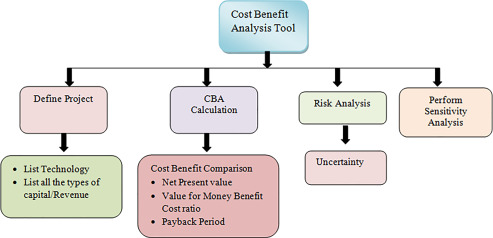

Steps in Conducting Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Identification of the Project or Policy: Define the activity being evaluated (e.g., building a dam, creating a national park, introducing pollution control).

- Listing of Costs and Benefits: Identify direct, indirect, and external costs/benefits.

- Quantification: Estimate the magnitude of these impacts (e.g., hectares of forest lost, tons of CO₂ avoided).

- Monetization: Assign monetary values using market prices or economic valuation techniques.

- Discounting: Convert future costs and benefits into present values using an appropriate discount rate.

- Comparison: Calculate Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), or Benefit-Cost Ratio (BCR).

- Decision-making: Decide whether to proceed, modify, or reject the project.

Costs and Benefits in Environmental Context

Costs

- Direct Costs: Construction expenses, operation, and maintenance costs.

- Environmental Costs: Loss of biodiversity, deforestation, pollution, soil degradation.

- Social Costs: Displacement of people, health hazards, loss of livelihoods.

- Opportunity Costs: Alternative uses of land, water, or resources forgone.

Benefits

- Direct Benefits: Agricultural productivity, energy generation, water supply.

- Environmental Benefits: Reduced emissions, improved air/water quality, ecosystem restoration.

- Social Benefits: Employment generation, poverty alleviation, better health outcomes.

- Avoided Costs: Damage avoided by preventing floods, soil erosion, or climate-related disasters.

Techniques of Environmental Valuation for CBA

A major challenge in environmental CBA is monetizing non-market goods (like clean air, biodiversity, or scenic beauty). Economists use specific techniques:

- Market-Based Valuation: For goods traded in markets (timber, fish).

- Replacement Cost Method: Cost of replacing lost ecosystem services (e.g., water treatment plants to replace natural wetlands).

- Hedonic Pricing: Valuing environmental quality through differences in property prices (e.g., houses near green spaces).

- Travel Cost Method: Estimating recreational value of forests, lakes, or parks by travel expenses incurred by visitors.

- Contingent Valuation: Using surveys to ask people their willingness to pay (WTP) for preserving an environmental asset or willingness to accept (WTA) compensation for its loss.

Application of CBA in Environmental Management

1. Project Appraisal for Infrastructure Development

When evaluating large projects such as dams, highways, or industrial zones, CBA considers environmental impacts:

- Example: A dam project may generate electricity (benefit) but submerge forests and displace communities (cost). CBA helps weigh whether benefits exceed costs when social and ecological values are included.

2. Pollution Control Policies

Governments use CBA to decide the stringency of pollution regulations. For instance, installing scrubbers in factories has costs, but the benefits include reduced health costs, fewer sick days, and improved ecosystem services.

3. Conservation Programs

CBA evaluates whether setting aside land for national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, or afforestation provides greater long-term benefits (tourism, carbon sequestration, biodiversity) compared to alternative land uses (mining or agriculture).

4. Climate Change Mitigation

Investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, or carbon capture are evaluated through CBA by comparing upfront costs with benefits of reduced greenhouse gas emissions, avoided climate damage, and health improvements.

5. Urban Environmental Management

Policies like waste recycling programs, green transport systems, or rainwater harvesting can be analyzed using CBA to justify investments based on long-term savings and environmental gains.

Advantages of Using CBA in Environmental Management

- Rational Decision-making: Provides a systematic framework for comparing alternatives.

- Captures Externalities: Incorporates environmental and social costs often ignored in traditional economic analysis.

- Resource Allocation: Helps prioritize projects with the greatest net social benefit.

- Transparency: Makes trade-offs explicit, enabling public debate.

- Policy Justification: Provides evidence-based support for environmental regulations and conservation initiatives.

Limitations and Challenges

- Valuation Difficulties: Many environmental goods (biodiversity, cultural values) are hard to quantify in monetary terms.

- Uncertainty and Risk: Long-term ecological impacts (like climate change) are uncertain, making projections difficult.

- Choice of Discount Rate: High discount rates undervalue future environmental benefits, biasing decisions against conservation.

- Distributional Issues: CBA focuses on aggregate net benefits but may ignore how costs and benefits are distributed across different social groups (e.g., displacement of indigenous people).

- Ethical Concerns: Monetizing life, species, or ecosystems raises moral questions.

Conclusion

Cost-Benefit Analysis is a powerful tool for evaluating projects and policies, ensuring that economic development does not come at the expense of environmental sustainability. By monetizing environmental benefits and costs, it allows decision-makers to weigh trade-offs, allocate resources efficiently, and promote sustainable development.

However, CBA is not without limitations. Valuation challenges, uncertainty, discounting, and ethical concerns must be addressed carefully. In practice, CBA should be complemented with other approaches such as multi-criteria analysis, participatory decision-making, and precautionary principles to capture the broader social and ecological dimensions.

Applied judiciously, CBA can serve as a bridge between economics and ecology, helping society choose pathways that maximize human welfare while conserving the environment for future generations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.