By Vihaan Gite

ABSTRACT

This lecture material critically examines fertility trends across the globe, focusing on essential demographic indicators, the underlying socioeconomic and cultural determinants of change, and the resulting policy challenges. The discussion begins by defining core measures such as the Total Fertility Rate (TFR), the Crude Birth Rate (CBR), and the concept of Replacement Level Fertility (approximately 2.1). It highlights the universal trend of fertility decline, contextualized by the Demographic Transition Model, illustrating the transition from high to low birth rates. The analysis then investigates the principal drivers of this transformation, including female education and empowerment, increased access to family planning, and urbanization. Finally, the module addresses the critical planning implications of both rapid decline (e.g., aging populations) and high fertility (e.g., resource strain), concluding with the necessity of integrating fertility data into sustainable development policy.

1. INTRODUCTION: Context and Significance

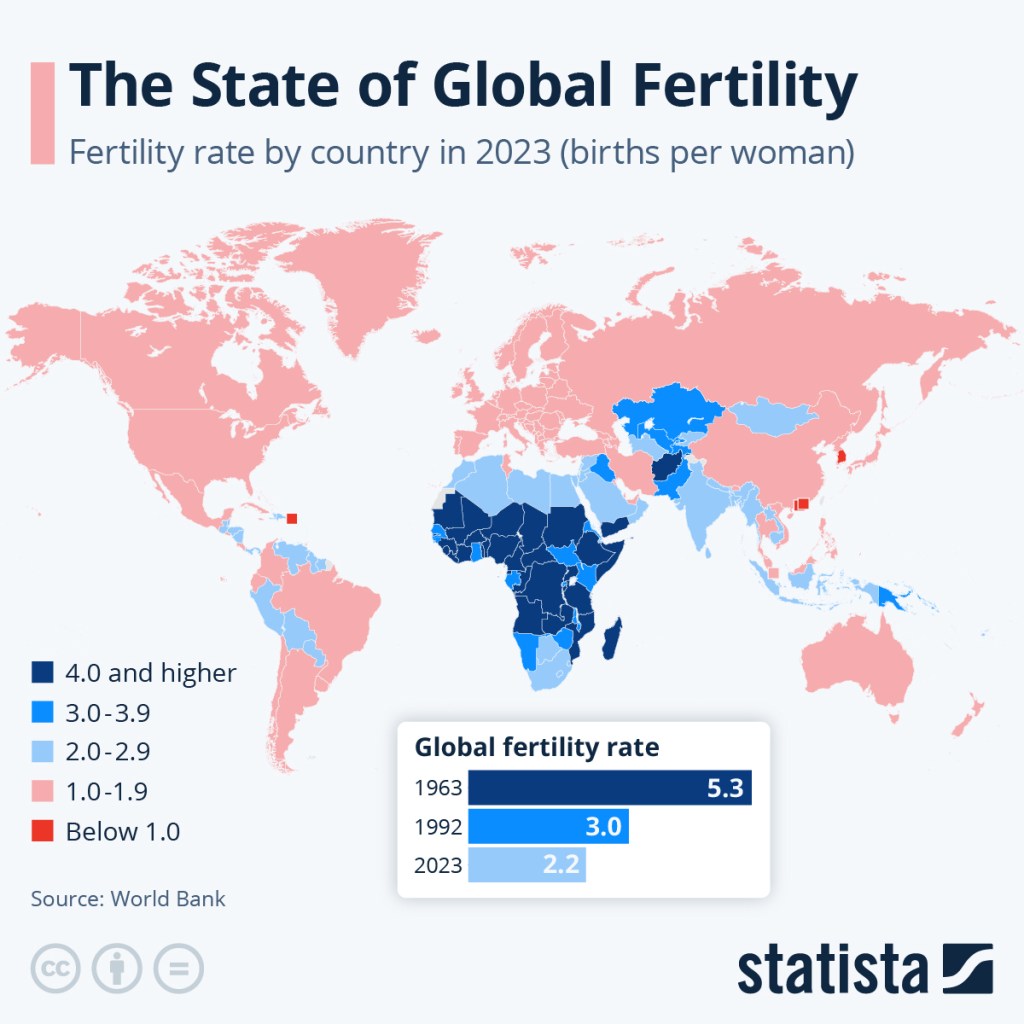

The trajectory of a nation’s development is inextricably linked to its population dynamics, of which fertility—the actual reproductive performance of a population—is a foundational component. Fertility trends reflect profound societal shifts in health, education, economic structure, and gender roles. Over the past century, the global population has witnessed an unprecedented and widespread decline in birth rates, a phenomenon that has dramatically reshaped the age structures of both developed and developing countries. According to the United Nations Population Division (official source), the global average TFR has fallen from approximately 5.0 children per woman in 1950 to around 2.3 in recent estimates, signaling a major transition.

- Policy Relevance: The significance of accurately charting and understanding fertility trends extends into every realm of governance. Low fertility in industrialized nations fuels concerns over aging populations and pension solvency, while persistently high fertility in parts of the Global South strains resources and infrastructure, contributing to a youth bulge.

- Purpose: This material aims to dissect the core measures and mechanisms driving these shifts, using established academic frameworks and reliable demographic data to illuminate the complexities of the modern fertility landscape and its implications for effective urban and regional planning.

2. CORE DEMOGRAPHIC DEFINITIONS AND MEASURES

To analyse fertility, specific, internationally recognized metrics are used:

| Measure | Definition | Significance |

| Total Fertility Rate (TFR) | The average number of children a woman would have over her lifetime, given current age-specific fertility rates. | The most comprehensive measure for comparing fertility across time and regions. |

| Crude Birth Rate (CBR) | The number of live births per 1,000 people in a given year. | A simple, initial measure of fertility, though sensitive to the population’s age structure. |

| Age-Specific Fertility Rate (ASFR) | The number of live births per 1,000 women in a specific age group (e.g., 20-24 years). | Provides detailed insight into when women are having children (timing and tempo). |

| Gross Reproduction Rate (GRR) | The average number of daughters a woman would have in her lifetime, used for population replacement analysis. | Used to estimate the pure biological potential for population replacement. |

| Replacement Level Fertility | The TFR required to maintain a stable population size, excluding migration. Conventionally set at approximately 2.1 children per woman. | The critical threshold. TFR below 2.1 indicates long-term population contraction. |

3. THE FRAMEWORK OF FERTILITY CHANGE

The universal decline in fertility is analyzed through two major theoretical models: the classical framework of the Demographic Transition Model (DTM) and the more recent conceptualization of the Second Demographic Transition (SDT).

3.1 The Demographic Transition Model (DTM)

The DTM describes the historical shift from high birth rates (HBR) and high death rates (HDR) to low birth rates (LBR) and low death rates (LDR) as a society industrializes and modernizes.

| Stage | Birth Rate | Death Rate | Population Growth | Characteristics |

| Stage 1 (Pre-Industrial) | High | High | Slow/Zero | Found historically; high child mortality, dependence on agriculture. |

| Stage 2 (Early Transitional) | High | Rapidly Falling | Very Rapid | Public health improves, sanitation advances; Population Explosion due to falling death rates. |

| Stage 3 (Late Transitional) | Falling | Low | Slowing | Fertility begins to drop due to social and economic changes. |

| Stage 4 (Post-Industrial) | Low | Low | Stable/Zero | Modern developed economies; TFR often at or below Replacement Level (2.1). |

3.2 Global Trends and Milestones

- Developed Nations: Most industrialized countries (e.g., Japan, Germany, Italy) are in Stage 4, with TFRs significantly below 1.5, leading to rapid population aging.

- Developing Nations (The “Catch-Up”): Many large economies (e.g., India, Brazil) have experienced a much faster fertility decline than historically seen in Western countries, largely due to accelerated access to technology and information. For example, India’s TFR officially dropped to 2.0 as per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, 2019-21), marking a historic point below replacement level.

- Outlier Regions: Parts of Sub-Saharan Africa remain in Stage 2/Early Stage 3, characterized by TFRs still high (e.g., 5.0+), leading to a significant youth bulge and continued rapid population growth.

4. DETERMINANTS OF FERTILITY DECLINE

The decision to have fewer children is driven by powerful, inter-connected societal shifts:

- Socioeconomic Development and Education:

- Female Education: This is the single strongest and most consistent correlate with fertility decline. Higher education leads to delayed marriage, postponed first birth, greater agency in family planning, and changed life aspirations.

- Economic Cost of Children: In agricultural societies, children are economic assets (labor). In industrialized/urban societies, they become economic liabilities (cost of education, healthcare, etc.), incentivizing smaller families.

- Health and Mortality:

- Decline in Infant and Child Mortality: As fewer children die in infancy, parents no longer need “insurance births” to ensure some children survive to support them in old age. This increases confidence in family planning.

- Access to Family Planning and Contraception:

- The widespread availability and knowledge of modern contraceptive methods enable individuals and couples to translate their desire for fewer children into reality. Government policies promoting informed choice and access are key enablers.

- Urbanization and Changing Social Norms:

- Urban Lifestyles: Urbanization is associated with less living space, different social networks, and access to mass media that promotes modern, smaller-family ideals.

- Women’s Labor Force Participation: Increased participation in non-agricultural work competes with time for child-rearing and increases the opportunity cost of having children.

5. POLICY CHALLENGES AND IMPLICATIONS

Fertility trends present a duality of profound policy challenges globally, requiring sharply different governmental responses:

5.1 Challenges of Sub-Replacement Fertility (TFR < 2.1)

This trend, typical of SDT countries, leads to an acute imbalance in the Old-Age Dependency Ratio (the ratio of retirees to working-age adults).

- Aging Population and Economic Strain: A shrinking base of young workers must support an expanding, longer-lived cohort of retirees.

- Implication: Solvency crisis for public pension and social security systems; soaring costs for specialized elderly healthcare.

- Policy Response (Pronatalism): Governments implement policies designed to encourage births, such as:

- Generous cash incentives and child benefits (e.g., France, Sweden).

- Long, paid parental leave for both parents.

- Subsidized, high-quality childcare and kindergarten access.

- Immigration: Used as a compensatory measure to fill workforce gaps and counteract population shrinkage.

5.2 Challenges of High Fertility (TFR >> 2.1)

This trend, typical of nations still in DTM Stage 2/Early Stage 3, is characterized by a significant Youth Bulge (a very large proportion of the population under age 15).

- Resource Strain and Developmental Hurdles: Rapid population growth consumes development gains and strains infrastructure.

- Implication: Overburdened and low-quality education systems; massive demand for job creation that often outstrips economic growth; increased pressure on basic services (water, sanitation, housing).

- Policy Response (Family Planning): Governments focus on managing and slowing growth:

- Massive investment in female education and keeping girls in school.

- Strengthening reproductive health services to ensure access to contraception and prevent unwanted pregnancies.

- Prioritizing maternal and child health to further drive down infant mortality, thereby reducing the “insurance motive” for high fertility.

CONCLUSION

The global narrative of fertility is one of profound and sustained transformation, shifting the demographic center of gravity for nearly every nation. The decline in TFR is a testament to human development—a success story largely attributable to the rising status of women and advancements in public health. While the DTM explains the initial, economically rational shift away from high fertility, the SDT is essential for understanding the sustained sub-replacement fertility and the value-driven decision-making in highly developed societies.

The primary task for policymakers remains the effective utilization of reliable, officially generated fertility data (from Census bureaus and national health surveys) to anticipate future population structures. Effective governance necessitates tailored strategies: promoting family-friendly environments in SDT nations to mitigate aging and simultaneously ensuring robust education and health infrastructures in high-fertility regions to capture the Demographic Dividend. Future census exercises must be refined to capture emerging household formations and values (as suggested by the SDT) to ensure that policy remains responsive to the dynamic and complex demographic realities of the 21st century.

REFERENCES

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. (Provides official global TFR data and projections).

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. (2021). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21. (Example of official, national-level data used for TFR calculation).

- Bongaarts, J. (2003). Completing the Fertility Transition in the Developing World: The Role of Contraception and Education. Population Council. (Key academic analysis on the determinants of fertility decline).

- World Bank Group. (2020). Demographic Dividends and the Power of Women’s Education. (Official report linking human capital, TFR, and economic growth).

You must be logged in to post a comment.