By Kavita Dehalwar

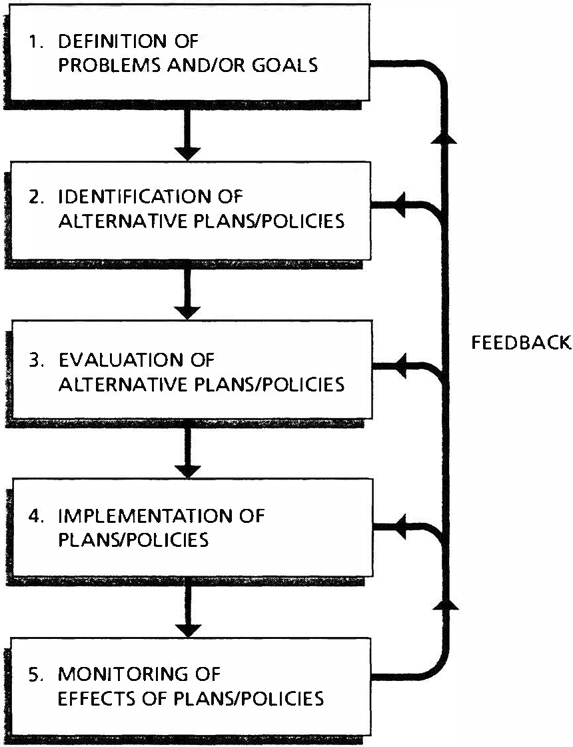

The Rational Urban Planning Process is a systematic and methodical approach used to guide urban development and city management. It is based on logical reasoning, data-driven decision-making, and a structured series of steps that ensure urban plans are comprehensive, practical, and sustainable. This process is often used by urban planners, city managers, and policymakers to design cities or manage growth in a way that maximizes benefits for residents, businesses, and the environment while minimizing potential negative impacts.

Key Components of the Rational Urban Planning Process

Key Components of the Rational Urban Planning Process

- Problem Identification and Definition

The first step involves identifying and clearly defining the urban issues or problems that need to be addressed. This could range from housing shortages and traffic congestion to environmental degradation and infrastructure deficiencies. Clear problem definition allows the planning team to establish focused objectives for the planning process. - Data Collection and Analysis

Planners gather comprehensive data about the city, which may include demographic statistics, land use patterns, environmental data, and economic conditions. Analyzing this data helps planners understand the current situation, identify trends, and forecast future changes. This phase often involves mapping, surveys, and field studies. - Goal Setting

Based on the problem definition and data analysis, planners set specific, measurable goals for the urban plan. These goals may include reducing traffic, increasing green spaces, or improving public transport efficiency. It’s essential that these goals align with the broader vision of the city and the needs of its residents. - Generating Alternative Solutions

In the rational planning model, a variety of alternative solutions or plans are developed to address the defined problems. These alternatives are based on the collected data and are designed to achieve the goals set in the previous step. Each alternative is typically distinct, offering different strategies or priorities, such as emphasizing public transportation over private car use or increasing high-density housing versus preserving more open spaces. - Evaluating Alternatives

Once a range of alternatives has been developed, they are evaluated based on their potential impacts, costs, benefits, and feasibility. This evaluation uses quantitative and qualitative methods to assess how well each alternative aligns with the planning goals. Cost-benefit analysis, environmental impact assessments, and social equity assessments are some tools used in this step. Stakeholder feedback may also be integrated to refine the options. - Selecting the Best Alternative

The rational planning process aims to identify the “optimal” solution from the evaluated alternatives. This is the option that best meets the identified goals, maximizes benefits, and minimizes costs or negative impacts. The selected plan may not be perfect but should represent the most balanced and feasible approach. - Implementation of the Plan

Once the best alternative is selected, planners develop a detailed action plan that outlines how the urban plan will be implemented. This step involves creating policies, regulations, and strategies that ensure the plan is executed efficiently. It may also include designing timelines, allocating budgets, and identifying key agencies or stakeholders responsible for various aspects of the implementation. - Monitoring and Evaluation

After implementation, the plan must be regularly monitored to ensure that it is achieving the desired outcomes. Evaluation involves comparing actual results against the goals and objectives set earlier in the process. If the plan is not performing as expected, adjustments can be made. This continuous monitoring ensures that the urban plan remains responsive to changing conditions and community needs.

Characteristics of the Rational Urban Planning Process

- Systematic: The process is highly structured and follows a step-by-step methodology, ensuring no aspect of urban planning is overlooked.

- Goal-Oriented: Each step is driven by clearly defined goals and objectives, which guide decision-making throughout the process.

- Data-Driven: Decisions are based on empirical data, research, and analysis, which helps avoid subjective or politically driven choices.

- Flexibility in Alternatives: Multiple solutions are considered, allowing for a range of options to be explored and evaluated before selecting the best one.

- Predictive: The process involves forecasting future trends and conditions, enabling planners to anticipate challenges and opportunities.

Criticism of the Rational Planning Process

Despite its logical structure, the rational planning process has faced criticism, particularly in the context of urban planning:

- Complexity of Urban Environments: Cities are dynamic and complex systems where social, economic, and environmental factors are interrelated. The rational approach can sometimes oversimplify this complexity, assuming that all variables can be measured and controlled.

- Time-Consuming: The thoroughness of data collection, analysis, and evaluation can make the rational process lengthy, sometimes leading to delays in decision-making or action.

- Limited Flexibility: The step-by-step nature of the process may not always allow for the flexibility needed to respond to unexpected changes, such as political shifts or economic crises.

- Stakeholder Exclusion: Critics argue that the rational planning process can overlook the voices of marginalized groups if the focus is solely on data and technical analysis, without sufficient community input or consideration of social equity.

- Over-Emphasis on Quantitative Data: While data-driven decision-making is a strength, the process sometimes places too much emphasis on quantitative analysis, neglecting qualitative factors like cultural significance or social well-being that are harder to measure.

Application in Modern Urban Planning

Today, the rational urban planning process is often blended with other planning models to address some of its limitations. For example:

- Participatory Planning: Involves stakeholders, including local communities, in each step of the process, ensuring their voices are heard and their needs are reflected in the final plan.

- Incremental Planning: Allows for smaller, more flexible decisions to be made, adjusting the plan as new information becomes available.

- Sustainability Planning: Incorporates environmental considerations from the outset, aiming to create cities that are not only functional but also ecologically responsible.

Conclusion

The Rational Urban Planning Process is a valuable tool for systematically addressing the challenges of urban growth and development. Its emphasis on logical, data-driven decision-making helps create well-thought-out, practical solutions. However, in modern contexts, it is often used in combination with other models to address its limitations and ensure more inclusive, flexible, and adaptive urban planning outcomes.

References

Baum, H. S. (1996). Why the rational paradigm persists: Tales from the field. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 15(2), 127-135.

de Smit, J., & Rade, N. L. (1980). Rational and non-rational planning. Long Range Planning, 13(2), 87-101.

Gezelius, S. S., & Refsgaard, K. (2007). Barriers to rational decision-making in environmental planning. Land use policy, 24(2), 338-348.

Rothblatt, D. N. (1971). Rational planning reexamined. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 37(1), 26-37.

Stuart, D. G. (1969). Rational urban planning: problems and prospects. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 5(2), 151-182.

You must be logged in to post a comment.