By Kavita Dehalwar & Devraj Verma

Research Associates, Track2Training, India

Sustainable development and resilient transport systems form the backbone of well-functioning, future-ready cities. As urban populations expand and environmental pressures intensify, cities must adopt planning approaches that balance mobility needs, ecological responsibility, and social well-being. Modern urban planning is no longer only about accommodating growth—it is about guiding growth in a way that is resource-efficient, inclusive, safe, and adaptive to climate and socio-economic challenges.

1. Sustainable Development as a Foundation for Urban Planning

Sustainable development provides a long-term framework to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to thrive. In urban systems, this translates into strategies that promote efficient land use, environmental protection, social equity, and economic vitality.

Recent scholarship emphasizes the role of sustainable building practices, waste management innovation, and nature-based solutions in shaping resilient urban futures. For example, research on solid waste management and AI-enabled environmental planning (Sharma et al., 2024; Dehalwar & Sharma, 2026; Sharma et al., 2025) shows how technological interventions can improve resource efficiency and decrease ecological burdens. Similarly, studies on green buildings and prefabricated construction (Sharma et al., 2025) underscore how sustainable construction practices reduce emissions, enhance energy performance, and improve neighbourhood livability.

Urban planning also increasingly recognizes the interconnectedness of environmental health, climate adaptation, and social justice. Work by Lucero-Prisno et al. (2025), for instance, links climate disasters with migration, health impacts, and food security—reminding planners that sustainability includes human resilience and equity, not just environmental metrics.

2. Resilient Transport as a Catalyst for Sustainable Cities

Transportation is one of the most influential determinants of urban form, environmental quality, and social accessibility. A resilient transport system ensures that mobility is safe, reliable, adaptable, and environmentally responsible, even amid disruptions such as climate events or population surges.

A robust body of research highlights the importance of transport resilience within sustainable development. For instance, last-mile logistics using generative AI and digital twins (Sharma, 2025) demonstrates how advanced technologies can optimize electric vehicle integration and reduce carbon footprints. Similarly, studies on first- and last-mile accessibility in transit-oriented development (TOD) (Yadav et al., 2025) emphasize the need to design seamless connections that support public transport usage.

Pedestrian and road safety remain crucial components of resilient transport. The systematic review by Sharma and Dehalwar (2025) on urban pedestrian safety reveals significant gaps in policy and infrastructure that must be addressed to safeguard vulnerable road users. Moreover, surrogate safety analysis research (Sharma, Singh & Dehalwar, 2024) shows how advanced modelling can help planners prevent crashes before they occur.

3. Integrating Sustainability and Transport Resilience in Urban Planning

Good urban planning requires a holistic approach that unites sustainable development principles with resilient transport strategies. Transit-oriented development, in particular, emerges as a powerful mechanism to achieve this integration. Scholarly work (Sharma & Dehalwar, 2025; Sharma, Kumar & Dehalwar, 2024) demonstrates how TOD encourages compact, mixed-use growth, reduces car dependence, and stimulates economic development—creating greener and more inclusive cities.

Resilient transport systems also support sustainability by:

- Reducing emissions through shared mobility, electrification, and efficient public transit.

- Improving social equity by ensuring safe and accessible mobility for seniors, women, and marginalized groups (Sharma & Dehalwar, 2025; Dehalwar & Sharma, 2024).

- Enhancing disaster preparedness through robust infrastructure and adaptive planning.

Conclusion

Sustainable development and resilient transport are essential, mutually reinforcing components of good urban planning. Together, they enable cities to reduce environmental impacts, improve livability, promote social justice, and withstand future uncertainties. Integrating these principles into policies, infrastructure investment, and spatial planning will help cities transition toward healthier, safer, and more prosperous urban futures.

References

Lalramsangi, V., Garg, Y. K., & Sharma, S. N. (2025). Route choices to access public open spaces in hill cities. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 16(2), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/09754253251388721

Lodhi, A. S., Jaiswal, A., & Sharma, S. N. (2024). Assessing bus users’ satisfaction using discrete choice models: A case of Bhopal. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, 9(11), 437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-024-01652-w

Sharma, S. N. (2025). Generative AI and digital twins for sustainable last-mile logistics: Enabling green operations and electric vehicle integration. In A. Awad & D. Al Ahmari (Eds.), Accelerating logistics through generative AI, digital twins, and autonomous operations (Chapter 12). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3373-7006-4.ch012

Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2025). A systematic literature review of pedestrian safety in urban transport systems. Journal of Road Safety, 36(4), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.33492/JRS-D-25-4-2707507

Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2025). A systematic literature review of transit-oriented development to assess its role in economic development of cities. Transportation in Developing Economies, 11(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40890-025-00245-1

Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2025). Examining the inclusivity of India’s National Urban Transport Policy for senior citizens. In D. S.-K. Ting & J. A. Stagner (Eds.), Transforming healthcare infrastructure (1st ed., pp. 115–134). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003513834-5

Sharma, S. N., & Dehawar, K. (2025). Review of land use transportation interaction model in smart urban growth management. European Transport / Trasporti Europei, 103, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17315313

Sharma, S. N., Kumar, A., & Dehalwar, K. (2024). The precursors of transit-oriented development. Economic and Political Weekly, 59(14), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10939448

Sharma, S. N., Singh, D., & Dehalwar, K. (2024). Surrogate safety analysis: Leveraging advanced technologies for safer roads. Suranaree Journal of Science and Technology, 31(4), 010320(1–14). https://doi.org/10.55766/sujst-2024-04-e03837

Yadav, K., Dehalwar, K., & Sharma, S. N. (2025). Assessing the factors affecting first and last mile accessibility in transit-oriented development: A literature review. GeoJournal, 90, 298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-025-11546-8

Yadav, K., Dehalwar, K., Sharma, S. N., & Yadav, S. (2025). Understanding user satisfaction in last-mile connectivity under transit-oriented development in Tier 2 Indian cities: A climate-sensitive perspective. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.

Dehalwar, K., & Sharma, S. N. (2024). Politics in the name of women’s reservation. Contemporary Voice of Dalit. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455328X241262562

Dehalwar, K., & Sharma, S. N. (2024). Social injustice inflicted by spatial changes in vernacular settings: An analysis of published literature. ISVS e-journal, 11(9). https://isvshome.com/pdf/ISVS_11-09/ISVSej_11.09.07.pdf

Kumar, G., Vyas, S., Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2025). Urban growth prediction using CA–ANN model and spatial analysis for planning policy in Indore city, India. GeoJournal, 90(3), 139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-025-11393-7

Patel, R. S., Taneja, S., Singh, J., & Sharma, S. N. (2024). Modelling of surface run-off using SWMM and GIS for efficient stormwater management. Current Science, 126(4), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v126/i4/463-469

Sharma, S. N. (2019). Review of most used urban growth models. International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 10(3), 397–405. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372478470

Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2023). Council of planning for promoting planning education and planning professionals. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 43(4), 748–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X231204568

Dehalwar, K., & Sharma, S. N. (Eds.). (2026). Deltas resilience: Nature-based solutions for sustainable development in India. Springer Nature. https://link.springer.com/book/9783032072399

Kumar, G., Vyas, S., Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2024). Challenges of environmental health in waste management for peri-urban areas. In M. Nasr & A. Negm (Eds.), Solid waste management (pp. 149–168). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60684-7_9

Lucero-Prisno, D. E. III, Ayuba, D., Akinga, A. Y., Olayinka, K. E., Precious, F. K., Ogaya, J. B., Sharma, S. N., … Kouwenhoven, M. B. N. (2025). Impact of climate disaster, migration and health risk on food security in Africa. In Advances in food security and sustainability. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.af2s.2025.08.003

Ogbanga, M. M., Sharma, S. N., Pandey, A. K., & Singh, P. (2025). Artificial intelligence in social work to ensure environmental sustainability. In M. Nasr, A. Negm, & L. Peng (Eds.), Artificial intelligence applications for a sustainable environment (pp. 1–??). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-91199-6_16

Sharma, S. N., Dehalwar, K., & Singh, J. (2024). Emerging techniques in solid waste management for a sustainable and safe living environment. In M. Nasr & A. Negm (Eds.), Solid waste management (pp. 29–51). Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60684-7_3

Sharma, S. N., Dehalwar, K., Jain, S., & Pandey, A. K. (2025). An assessment of the applications and prospects of AI tools in solid waste management. In M. Nasr, A. Negm, & L. Peng (Eds.), Artificial intelligence applications for a sustainable environment. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-91199-6_4

Sharma, S. N., Lodhi, A. S., Dehalwar, K., & Jaiswal, A. (2024). Life cycle assessment of recycled and secondary materials in the construction of roads. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1326(1), 012102. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1326/1/012102

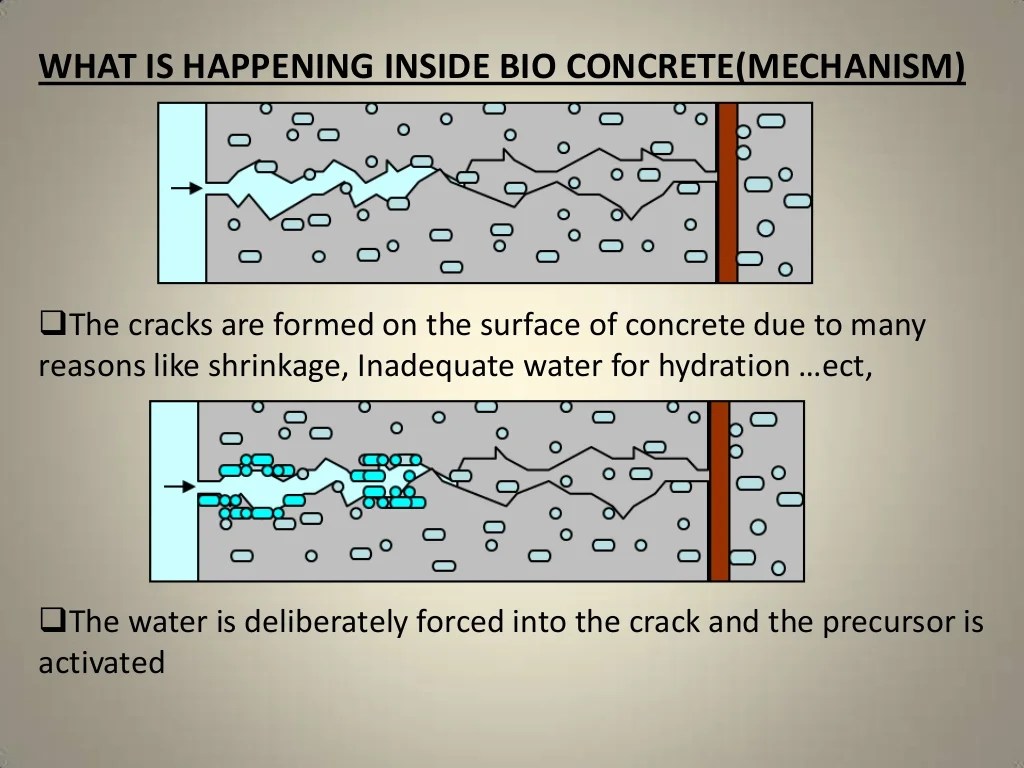

Sharma, S. N., Prajapati, R., Jaiswal, A., & Dehalwar, K. (2024). A comparative study of the applications and prospects of self-healing concrete / biocrete and self-sensing concrete. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1326(1), 012090. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1326/1/012090

Sharma, S. N., Singh, S., Kumar, G., Pandey, A. K., & Dehalwar, K. (2025). Role of green buildings in creating sustainable neighbourhoods. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1519(1), 012018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1519/1/012018

Sharma, S. N., Dehalwar, K., Singh, J., & Kumar, G. (2025). Prefabrication building construction: A thematic analysis approach. In S. B. Singh, M. Gopalarathnam, & N. Roy (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Advances in Concrete, Structural, and Geotechnical Engineering—Volume 2 (pp. 405–428). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-0751-8_28

You must be logged in to post a comment.