By Kavita Dehalwar

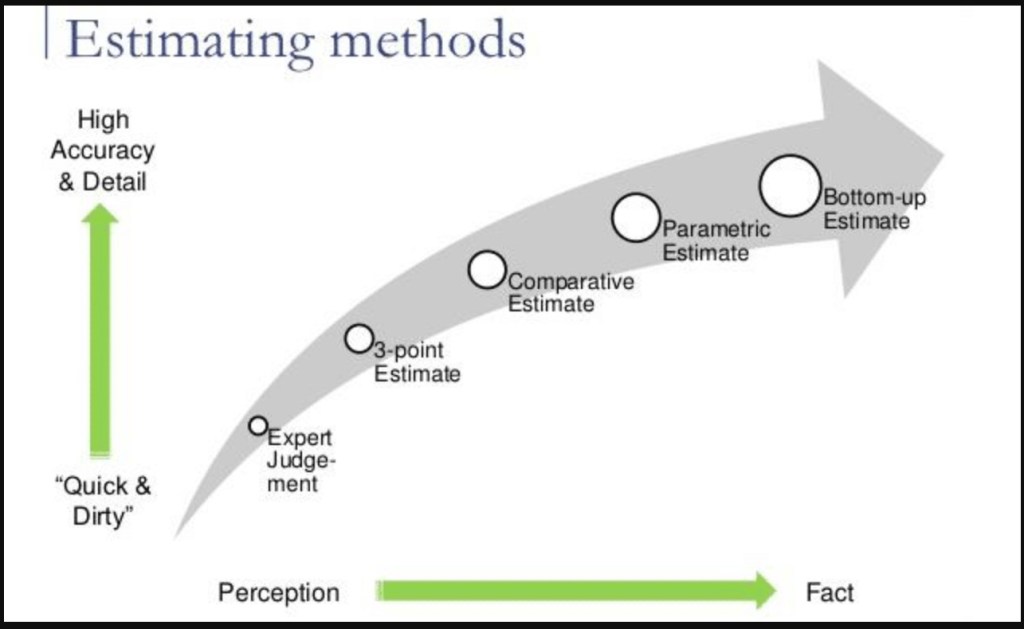

Estimation is a critical activity in construction and project management, as it directly influences decision-making, budgeting, scheduling, and resource allocation. The attached image clearly illustrates how estimating methods evolve from quick, perception-based approaches to highly detailed, fact-driven techniques, with a corresponding increase in accuracy and level of detail. This progression reflects the maturity of project information and the purpose for which the estimate is prepared.

The horizontal axis in the image represents a shift from perception to fact, while the vertical axis highlights the movement from “quick and dirty” estimates to high accuracy and detail. As projects move forward, estimation methods transition along this curve.

1. Expert Judgment Estimate

At the earliest stage of a project, expert judgment is often the primary estimation method. This approach relies on the experience, intuition, and professional knowledge of experts who have worked on similar projects.

Characteristics:

- Based largely on perception and past experience

- Minimal data or documentation required

- Very fast and inexpensive

Applications:

- Conceptual planning

- Initial idea screening

- Early discussions with stakeholders

Limitations:

- Highly subjective

- Accuracy depends heavily on expert competence

- Difficult to justify quantitatively

This method is positioned at the far left of the image, emphasizing its low accuracy but high speed. It is useful for rough direction-setting rather than firm decision-making.

2. Three-Point Estimate

The three-point estimate improves upon pure expert judgment by incorporating uncertainty into the estimation process. Instead of a single value, three scenarios are considered:

- Optimistic (O)

- Most likely (M)

- Pessimistic (P)

These values are combined to produce a weighted average estimate.

Characteristics:

- Accounts for risk and uncertainty

- More structured than expert judgment

- Still relatively quick

Applications:

- Risk assessment

- Early feasibility analysis

- Schedule and cost forecasting

Advantages:

- Reduces bias

- Encourages realistic thinking

Although still partially perception-based, this method moves slightly upward on the accuracy scale, as shown in the image.

3. Comparative Estimate

A comparative estimate (also known as analogous estimation) uses historical data from similar completed projects as a reference.

Characteristics:

- Relies on documented past projects

- Adjustments made for size, location, complexity, and inflation

- Moderately accurate

Applications:

- Feasibility studies

- Preliminary budgeting

- Alternative evaluation

Strengths:

- Faster than detailed estimation

- More objective than judgment-based methods

Weaknesses:

- Accuracy depends on similarity of reference projects

- Adjustments may introduce errors

In the image, comparative estimates occupy the mid-zone, representing a balance between speed and reliability.

4. Parametric Estimate

The parametric estimating method uses statistical relationships between variables to estimate cost or time. For example, cost per square meter, cost per bed, or cost per classroom.

Characteristics:

- Uses mathematical models and cost drivers

- Requires reliable historical data

- Scalable and repeatable

Applications:

- Large-scale projects

- Budget forecasting

- Institutional and infrastructure planning

Advantages:

- Higher accuracy than comparative estimates

- Data-driven and transparent

Limitations:

- Requires validated parameters

- Less effective for unique or complex designs

As shown in the image, parametric estimation is closer to the “fact” end of the spectrum, offering higher accuracy and greater confidence.

5. Bottom-Up Estimate

The bottom-up estimate represents the most detailed and accurate estimation method shown in the image. It involves breaking the project into individual components or work items and estimating each separately before aggregating the total cost.

Characteristics:

- Item-by-item quantity take-off

- Detailed rate analysis

- High time and effort requirement

Applications:

- Tendering and bidding

- Final project approval

- Cost control during execution

Advantages:

- Highest accuracy

- Strong justification and traceability

- Suitable for contracts and audits

Disadvantages:

- Time-consuming

- Requires complete drawings and specifications

This method appears at the far right and highest point in the image, clearly indicating maximum accuracy, detail, and factual basis.

The image conveys a powerful message: no single estimating method is universally best. Instead, the choice of method depends on:

- Project stage

- Availability of information

- Required accuracy

- Time and resources

Early-stage decisions benefit from fast, perception-based methods, while later stages demand rigorous, fact-based approaches. Attempting a bottom-up estimate too early can waste effort, while relying on expert judgment too late can lead to cost overruns.

Conclusion

The progression of estimating methods—from expert judgment to bottom-up estimation—reflects the natural evolution of project information and decision needs. As shown in the image, accuracy and detail increase as estimates move from perception to fact. Effective project management lies in selecting the right estimation method at the right time, ensuring informed decisions without unnecessary complexity.

Understanding this hierarchy of estimating methods enables engineers, planners, and project managers to balance speed, accuracy, and reliability, ultimately contributing to successful project outcomes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.