BY DAKSHITA NAITHANI

Prokaryotic life has dominated much of our planet’s evolutionary history, developing to fill nearly every possible environmental niche. Extremophiles are one of these. Extremophiles have been identified on Earth that can survive in conditions that were previously considered to be inhospitable to life. Heat, extremely acidic conditions, extreme pressure, and extreme cold are examples of extreme environments. The thermophiles were the first extremophiles to be discovered in the 1960s by Thomas Brock of Indiana University. He was investigating life in Yellowstone National Park’s super-hot water pools. He discovered tiny microorganism mats at Octopus Spring in 1965, when temperatures reached 175 degrees Fahrenheit. Thermus aquaticus was discovered, which led to the discovery of PCR and the creation of a new multibillion-dollar enterprise.

EXTREMOPHILES IN SALINITY: HALOPHILES

The halophiles live in high salt concentrations and are named after the Greek term for “salt-loving.” While the majority of halophiles belong to the archaea domain, some bacterial halophiles and eukaryotic species, such as the alga Dunaliella salina and the fungus Wallemia ichthyophaga, do not. Carotenoid chemicals give certain well-known species, such as bacteriorhodopsin, a red hue. They may be found in salty water bodies such as the Great Salt Lake in Utah, Owens Lake in California, the Dead Sea, and evaporation ponds, where the salt content is more than five times that of the ocean. They’re thought to be a viable contender for extremophiles living in Jupiter’s Europa and other comparable moons’ salty subsurface water oceans.

CELLULAR ADAPTATIONS BY HALOPHILES

High salt-in strategy

The high-salt-in approach protects halophiles from a saline environment by accumulating inorganic ions intracellularly and balancing the salt content in their surroundings through KCl influx. Cl- pumps, which are only found in halophiles and transfer them from the environment into the cytoplasm, are involved in this process. Extreme halophiles of the archaeal and bacterial families keep their osmotic equilibrium by concentrating K + inside their cells. The membrane-bound proton-pump bacteriorhodopsin works to accomplish this.

Low-salt, organic solute-in strategy

The high-salt-in approach necessitates physical modification of all macromolecules in order to survive in a very saline environment, which is incompatible with the survival of moderate halophiles that flourish in salinity-varying environments. Osmolytes protect microbial proteins against dissociation in low-salt water while also improving the bacteria’ tolerance to drastic changes in external saline conditions. Glycine betaine was the first bacterial osmolyte discovered in Halorhodospria halochloris.

The majority of halophiles are unable to thrive outside of their high-salt natural habitats. Many halophiles are so delicate that putting them in distilled water causes them to lyse due to the shift in osmotic circumstances. Halophiles include phototrophic, fermentative, sulfate-reducing, homoacetogenic, and methanogenic species in anaerobic conditions whereas in aerobic conditions include phototrophic, fermentative, sulfate-reducing, homoacetogenic, and methanogenic species.

The Haloarchaea, notably the Halobacteriaceae family, belong to the Archaea domain and make up the bulk of the population in hypersaline settings. The family currently has 15 recognised genera. Bacteria (mostly Salinibacter ruber) can make up to 25% of the prokaryotic community, although it usually makes up a considerably smaller portion of the overall population. In this habitat, the alga Dunaliella salina can sometimes thrive.

EXTREMOPHILES AT LOW NUTRIENT LEVELS: OLIGOTROPHS

An oligotroph is an organism that can survive in a low-nutrient environment. Oligotrophs are usually known for their sluggish development, low metabolic rates, and sparse population density. The settings are ones that provide little in the way of life support. Deep marine sediments, caverns, glacial and polar ice, deep underground soil, aquifers, and leached soils are examples of these habitats.

The cave-dwelling olm the bacteria Pelagibacter ubique, which is the most numerous creature in the seas and lichens with their incredibly low metabolism are all examples of oligotrophic species.

Caulobacter crescentus is an oligotrophic Gram-negative bacteria found in freshwater waterbodies. The whole cell functions as an integrated system in the control circuitry that controls and paces Caulobacter cell cycle development. As it orchestrates activation of cell cycle subsystems and Caulobacter crescentus asymmetric cell division, the control circuitry monitors the environment and the internal status of the cell, including the cell topology. The control system has been meticulously tuned as a whole system for reliable functioning in the face of internal stochastic noise and external unpredictability by evolutionary selection.

The bacterial cell’s control system is organised in a hierarchical manner. The signalling and control subsystem communicates with the outside world through sensory units that are mostly found on the cell surface. To adjust the cell to current conditions, the genetic network logic responds to signals received from the environment as well as internal cell status sensors.

ENVIRONMENT AND LOCATIONS

Oligotrophic lakes are often found in northern Minnesota, with deep clear water, stony or sandy bottoms, and minimal algae.

Oxygen levels are high throughout the water column in oligotrophic lakes. Cold water may store more dissolved oxygen than warm water, thus oligotrophic lakes’ deep regions remain quite cold. Low algal content also provides for more light penetration and less breakdown. Algae, zooplankton, and fish die and are degraded by bacteria and invertebrates at the bottom of the ocean. The process of breakdown consumes oxygen.

Locations

Oligotrophs and eutrophs coexist in natural ecosystems, and their proportions are determined by an individual’s capacity to prevail in a given environment. Despite their capacity to exist in low-nutrient settings, they may struggle to survive in nutritionally- rich ones. Most microorganisms are not well adapted to exist in nutrient-limited circumstances and frigid temperatures (below 5 °C), Antarctic habitats offer very little to sustain life. Some of the documented examples of oligotrophic environments in Antarctica are:

Lake Vostok, a freshwater lake cut off from the rest of the world by 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) of Antarctic ice, is often cited as a prime example of an oligotrophic ecosystem. Because of the lake’s severe oligotrophy, some people assume that sections of it are entirely sterile. This may be used as a model to simulate alien life investigations on frozen planets and other celestial worlds.

Oligotrophic soil environments

In general, nutrient availability decreases as the depth of the soil environment increases, since organic molecules degraded from detritus are swiftly eaten by other microorganisms on the surface, resulting in nutritional deficiency in the deeper levels of soil.

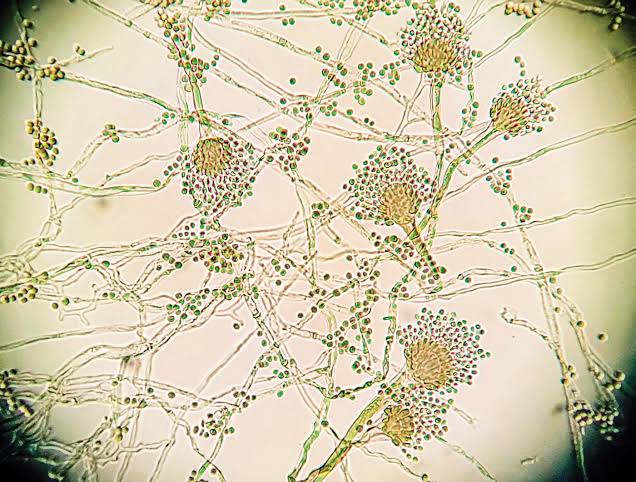

Collimonas is one of those species that may survive in an oligotrophic environment as it has the capacity to not only hydrolyze the chitin generated by fungus for nutrition, but also to create materials. Fungi are a prevalent element of the habitats where Collimonas thrives. In oligotrophic settings, reciprocal relationships are prevalent. Weathering also allows Collimonas to access electron sources from rocks and minerals.

The environment of soil in polar locations, such as the Antarctic and Arctic regions, is termed oligotrophic since the soil is frozen and biological activity is minimal. Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Cyanobacteria are the most common bacteria in frozen soil, with a tiny quantity of archaea and fungus. Under a wide range of low temperatures, actinobacteria can keep their metabolic enzymes active and continue their biochemical processes.

The following are the characteristics that a bacterium should have in order to be labelled as an oligotroph:

(a) Having a form with a high surface-to-volume ratio.

(b) Having an innate propensity for using metabolic energy for food absorption during phases of growth stagnation.

(c) Possessing nutrition absorption abilities that are expressed in a constitutive manner.

(d) Presence of a low-specificity, high-affinity transport mechanism that allows for simultaneous absorption of mixed substrate.

(e) Having systems for conserving nutrition after it has been absorbed.

Extremophiles and their products have revolutionised many aspects of our home and professional life, from household materials to molecular diagnostics. It is not unlikely that new and medically useful discoveries will be found in the realm of extremophile research; the potential of these organisms is so fresh and huge that their applications may be restricted only by imaginations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.