Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi (1927–2023) — affectionately known as B.V. Doshi — was a visionary Indian architect whose work bridged the worlds of tradition and modernity, and played a transformative role in shaping post-independence Indian architecture. He is widely celebrated for his humane approach to design, commitment to sustainability, and dedication to social housing, education, and culture. As the first Indian architect to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2018, Doshi’s legacy extends beyond buildings to influence generations of architects and planners.

🧒 Early Life and Education

B.V. Doshi was born on August 26, 1927, in Pune, Maharashtra, into a family of furniture makers. His early exposure to craftsmanship and traditional Indian aesthetics would later shape his architectural philosophy.

He studied at the Sir J.J. School of Architecture in Mumbai. However, it was his time in Europe during the early 1950s that had a profound impact on his thinking. Doshi worked under the legendary modernist Le Corbusier in Paris and later in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad, where he supervised major projects. He also collaborated with Louis Kahn on the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Ahmedabad.

🏛 Architectural Philosophy

B.V. Doshi’s architecture was deeply rooted in Indian traditions, climatic responsiveness, social responsibility, and human-centric design. He was a pioneer of modern Indian architecture who adapted modernist principles to the Indian context, fusing them with local materials, construction techniques, and cultural motifs.

Key principles in Doshi’s work:

- Synthesis of tradition and modernity

- Use of natural light and ventilation

- Community-focused spaces

- Affordable and low-cost housing

- Sustainability and local materials

- Spatial hierarchy and interactivity

- Celebration of courtyards, terraces, and verandas

🏠 Major Works

1. Aranya Low-Cost Housing, Indore (1989)

- One of Doshi’s most significant contributions to social housing.

- Designed for economically weaker sections, Aranya consists of over 6,500 residences.

- Encourages incremental growth, allowing families to expand or modify their homes.

- Winner of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (1995).

2. Indian Institute of Management (IIM), Bangalore (1977–1992)

- A sprawling campus of interlinked courtyards, stone corridors, and shaded walkways.

- The design reflects ancient Indian temples and educational spaces, creating contemplative environments.

3. CEPT University, Ahmedabad (1966 onwards)

- Doshi founded and designed the campus of Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT).

- A model of flexible, open, and democratic learning spaces.

- Features exposed brickwork, natural light, and a strong sense of place.

4. Tagore Memorial Hall, Ahmedabad (1967)

- Inspired by Indian temple architecture and brutalist aesthetics.

- Known for its bold concrete forms and acoustics suitable for performing arts.

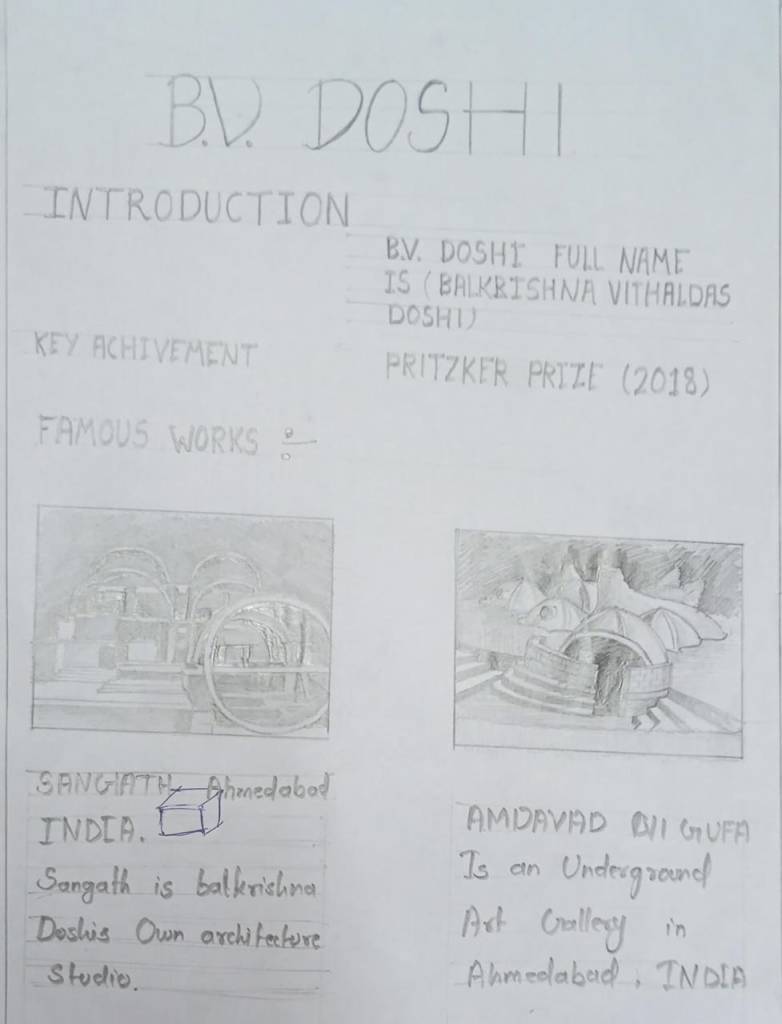

5. Amdavad ni Gufa (1995)

- An underground art gallery built in collaboration with artist M.F. Husain.

- Organic, cave-like forms with domes, mosaics, and undulating surfaces.

- A symbolic fusion of art, architecture, and nature.

6. Sangath, Ahmedabad (1981)

- Doshi’s own architectural studio.

- “Sangath” means “moving together” in Sanskrit.

- Built with sunken vaults, white mosaic surfaces, and shaded gardens, it reflects his approach to spatial experimentation and climate sensitivity.

🏆 Awards and Recognition

Pritzker Architecture Prize (2018)

- First Indian to win this prestigious award.

- Jury citation praised Doshi for “always designing for the backdrop of life… never architecture for architecture’s sake.”

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Gold Medal (2022)

- One of the world’s highest honors in architecture, awarded for lifetime achievement.

Other Recognitions:

- Padma Shri (1976)

- Padma Bhushan (2020)

- Aga Khan Award for Architecture (1995)

- Numerous honorary doctorates and international acclaim

🎓 Academic and Institutional Contributions

- Founder of CEPT University, a leading institution for architecture and planning in India.

- Taught and mentored generations of students.

- Served on design committees for national policy on architecture and planning.

- Advocated for architecture as a tool for social change.

📚 Writings and Influence

B.V. Doshi was a prolific speaker, thinker, and writer. His lectures, interviews, and writings reflect a deep philosophical engagement with architecture as a cultural, spiritual, and emotional practice.

His Work Emphasized:

- Timelessness over trends

- Contextual relevance over global styles

- Joyful spaces that promote human interaction

- Democracy in spatial design

- The spiritual dimension of built form

🕊 Death and Legacy

B.V. Doshi passed away on January 24, 2023, at the age of 95, in Ahmedabad. His passing marked the end of an era, but his ideas live on through his students, institutions, and built works.

Legacy Highlights:

- Regarded as the father of modern Indian architecture

- Celebrated globally as a humanist architect

- Inspired new generations to design with empathy, humility, and sustainability

- His buildings remain active, evolving spaces — not static monuments

🧠 Conclusion

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi was more than an architect — he was a philosopher, educator, and social reformer who believed in the power of design to improve lives. He showed the world how architecture could be deeply modern yet rooted in tradition; humble yet monumental; and sustainable yet imaginative.

You must be logged in to post a comment.