By Shashikant Nishant Sharma

The Burgess Concentric Zone Model, also known as the Concentric Ring Model or Concentric Zone Theory, is an urban land use model that was developed by sociologist Ernest W. Burgess in 1925. This model was part of a broader body of work aimed at understanding the structure and dynamics of cities, particularly in the context of rapid urbanization during the early 20th century. The model is one of the foundational theories in urban sociology and geography.

Overview of the Model

The Concentric Zone Model suggests that urban areas develop in a series of concentric rings or zones, each with distinct characteristics and functions. According to the model, a city grows outward from a central point, with different social groups and land uses segregating into these rings based on economic and social factors.

The Five Zones in the Concentric Zone Model

Burgess identified five distinct zones in the model:

- Zone 1: The Central Business District (CBD)

- Location and Function: At the center of the model is the Central Business District (CBD). This is the core of the city, where commercial, administrative, and cultural activities are concentrated.

- Characteristics: The CBD is characterized by high land values, a dense concentration of office buildings, retail spaces, and government institutions. Land use is predominantly non-residential due to the high cost of land.

- Dynamics: The CBD is highly accessible, with major transportation hubs often located here. It is the focal point of the city’s economy and a place where businesses compete for space, leading to vertical development (e.g., skyscrapers).

- Zone 2: The Zone of Transition

- Location and Function: Surrounding the CBD is the Zone of Transition. This area is in flux, often containing a mix of residential, commercial, and industrial uses.

- Characteristics: This zone is typically characterized by deteriorating housing, often occupied by low-income residents and new immigrants. It may also contain light industry, warehouses, and other activities that are incompatible with high-quality residential areas.

- Dynamics: The Zone of Transition is subject to change as the city expands and as land values increase in the CBD, causing commercial and industrial uses to spill over into this area. It is often associated with social problems such as poverty, crime, and overcrowding.

- Zone 3: The Zone of Working-Class Homes

- Location and Function: This zone is the first true residential area, located just outside the Zone of Transition.

- Characteristics: The Zone of Working-Class Homes is typically populated by factory workers and other blue-collar employees who work in the nearby industrial areas. Housing here is usually modest, but of better quality than in the Zone of Transition.

- Dynamics: Residents in this zone often have strong ties to their neighborhood and place of work, resulting in relatively stable communities.

- Zone 4: The Zone of Better Residences

- Location and Function: Further out is the Zone of Better Residences, where more affluent citizens live.

- Characteristics: This area is characterized by more spacious and higher-quality housing, with residents often comprising the middle class. The homes here are larger, and the neighborhoods are more suburban in character, with more green spaces and a lower population density.

- Dynamics: The residents in this zone often commute to work, either to the CBD or other areas of the city, and enjoy a higher quality of life compared to those in the inner zones.

- Zone 5: The Commuter Zone

- Location and Function: The outermost ring in the model is the Commuter Zone, sometimes referred to as the suburbs or exurbs.

- Characteristics: This zone is characterized by a predominantly residential landscape, with larger homes, more space, and a high level of owner-occupancy. It is typically populated by the upper-middle class and the wealthy.

- Dynamics: Residents in this zone often have longer commutes to work, typically traveling to the CBD or other business districts. This area represents the furthest extent of urban sprawl.

Key Assumptions and Criticisms

The Concentric Zone Model is based on several key assumptions:

- Uniform Land Use: The model assumes that land use is uniform across each zone and that each zone has a single, dominant function.

- Transportation: The model is premised on the idea that transportation is centrally focused, with people commuting into the CBD for work.

- Unidirectional Growth: It assumes that the city grows outward in a uniform manner from a central point.

While the model was pioneering in its time, it has faced criticism and has limitations:

- Over-Simplification: The model is often criticized for oversimplifying the complexities of urban development and for not accounting for the diversity and multi-nucleated nature of modern cities.

- Historical Context: The model was developed in the context of early 20th-century Chicago, which had specific social and economic conditions that may not apply universally.

- Ignored Factors: It doesn’t account for factors such as topography, governmental zoning laws, and the impact of transportation technologies (e.g., highways and railroads) that have influenced urban development.

Relevance Today

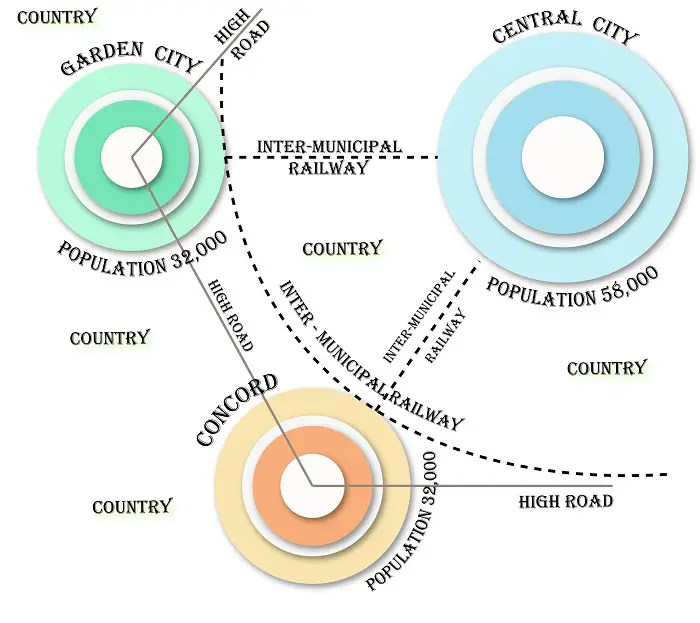

Despite its limitations, the Concentric Zone Model remains a foundational concept in urban geography and planning. It has influenced subsequent urban models, such as the Sector Model (Hoyt Model) and the Multiple Nuclei Model, which attempt to address some of the Concentric Zone Model’s limitations. It provides a basic framework for understanding the spatial organization of cities, particularly during periods of rapid industrialization and urbanization.

References

Balakrishnan, T. R., & Jarvis, G. K. (1991). Is the Burgess concentric zonal theory of spatial differentiation still applicable to urban Canada?. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 28(4), 526-539.

Ford, L. R. (1974). The Urban Housetype as an Illustration of the Concentric Zone Model: The Perception of Architectural Continuity. Journal of Geography, 73(2), 29-39.

Pineo, P. C. (1988). Socioeconomic status and the concentric zonal structure of Canadian cities. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 25(3), 421-438.

Schwirian, K. (2007). Ecological models of urban form: Concentric zone model, the sector model, and the multiple nuclei model. The blackwell encyclopedia of sociology.

Sharma, S. N., & Abhishek, K. (2015). Planning Issue in Roorkee Town. Planning.

You must be logged in to post a comment.