By Kavita Dehalwar

Neighborhood planning is a type of urban planning that aims to shape and guide new and existing neighborhoods. It’s a positive process that involves communities and professional urban planners working together to plan for new development that meets local needs. Neighborhood planning can involve creating a physical plan, or it can be an ongoing process.

Neighborhood planning is a grassroots, community-led process that allows residents and local stakeholders to actively participate in shaping the development and future of their local areas. This approach is built on the principle that local people are best placed to understand and plan for the needs of their community, ensuring that growth and change align with local values, needs, and preferences.

Key Aspects of Neighborhood Planning:

- Community Involvement: Neighborhood planning encourages wide participation from residents, businesses, and other local stakeholders. This includes workshops, public meetings, surveys, and other forms of consultation to gather diverse opinions and ideas.

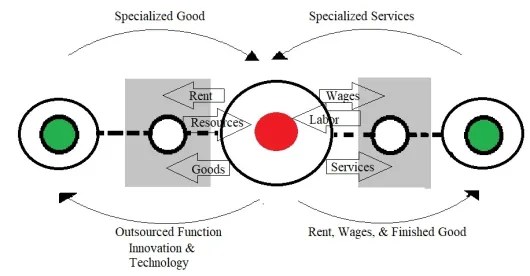

- Vision and Goals: The process typically begins with the community defining a clear vision for the future of their neighborhood. This vision guides the creation of specific goals related to housing, transportation, green spaces, economic development, and other local priorities.

- Policy Development: Based on the community’s vision, a set of policies and guidelines are developed to direct future development. These policies cover areas such as land use, building design, infrastructure, and environmental protection.

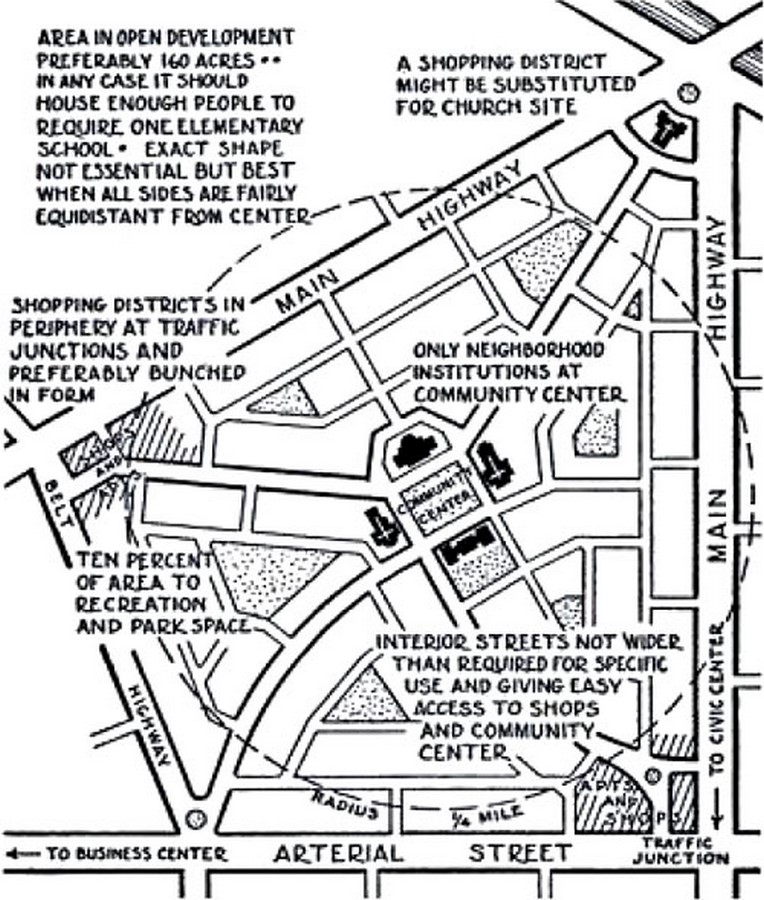

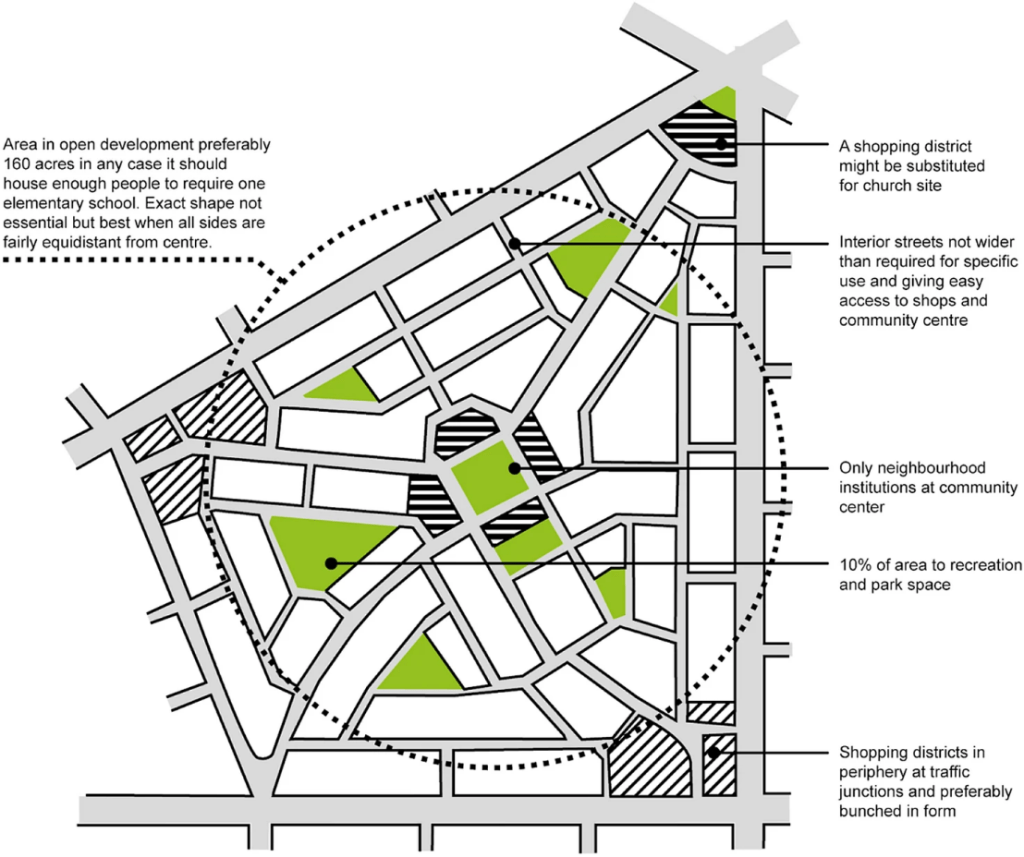

- Land Use Planning: A significant component of neighborhood planning is determining how land within the area should be used. This includes zoning decisions, the location of new homes, shops, or offices, and the protection of green spaces.

- Design Standards: Neighborhood plans often include design guidelines that ensure new developments are in harmony with the existing character of the area. This can include specifications for building height, materials, and architectural style.

- Implementation and Monitoring: Once a plan is adopted, it guides local government decisions on planning applications and development projects. The community also monitors progress and can make adjustments to the plan as needed.

- Legal Status: In many regions, neighborhood plans can become legally binding documents once they are approved through a community referendum and adopted by the local authority. This gives the plan significant influence over future development in the area.

Benefits of Neighborhood Planning:

- Empowerment: Residents have a direct say in the development of their community.

- Local Knowledge: Plans are more likely to reflect the unique needs and characteristics of the neighborhood.

- Sustainable Development: Local input can help ensure that growth is sustainable and enhances the quality of life.

- Conflict Reduction: Early community involvement can reduce conflicts over development decisions by addressing concerns upfront.

Challenges:

- Resource Intensive: The process can be time-consuming and require significant effort from volunteers.

- Complexity: Navigating planning regulations and technical details can be challenging for community groups.

- Representation: Ensuring that the plan reflects the views of the entire community, including marginalized groups, can be difficult.

Overall, neighborhood planning is a powerful tool for local communities to shape their environment, fostering a sense of ownership and ensuring that development aligns with local needs and values.

References

Dehalwar, K. Bridging the Gap: Community-Based and Workshop-Based Approaches to Address Rural and Urban Planning Issues.

Dehalwar, K. (Ed.). (2024). Basics of Research Methodology-Writing and Publication. EduPedia Publications Pvt Ltd.

Lowndes, V., & Sullivan, H. (2008). How low can you go? Rationales and challenges for neighbourhood governance. Public administration, 86(1), 53-74.

Subhashini, M., & Wickramaarachchi, N. (2022). Applicability of Perry’s neighbourhood concept in neighbourhood planning in Sri Lanka. International Planning Studies, 27(4), 370-393.

Dehalwar, K., & Sharma, S. N. (2023). Fundamentals of Area Appreciation and Space Perceptions A Textbook for Students of Architecture and Planning. Notion Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13325383

Sharma, S. N., & Dehalwar, K. (2024). Fundamentals of Planning and Design of Housing A textbook for Undergraduate Students of Architecture and Planning. Notion Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13325661

You must be logged in to post a comment.