Public policy making is the process through which governments design, implement, and evaluate decisions intended to address societal needs. Ideally, policies should be rational, evidence-based, and oriented toward the long-term welfare of citizens. However, in practice, policy formulation is constrained by political realities and economic limitations. Governments operate in complex environments shaped by competing interests, limited resources, ideological divides, and structural pressures.

Political and economic constraints influence not only the content of policies but also the pace of decision-making, the scope of implementation, and the effectiveness of outcomes. Understanding these constraints is essential for assessing why policies often deviate from their intended goals or fail to deliver expected results. This essay discusses in detail the political and economic constraints on policy making, their implications, and possible ways to address them.

Political Constraints on Policy Making

1. Electoral Pressures and Populism

Elected governments are heavily influenced by electoral cycles. Politicians often prioritize short-term, populist measures to secure votes rather than long-term structural reforms. For example, subsidies, loan waivers, or tax cuts may win immediate popularity but undermine fiscal stability and sustainable development. This short-termism hinders comprehensive and rational policy making.

2. Interest Groups and Lobbying

Powerful interest groups, such as industry associations, trade unions, or advocacy organizations, exert pressure on policymakers. Policies may reflect the demands of influential lobbies rather than the broader public interest. For instance, environmental regulations may be weakened due to pressure from industrial lobbies, even if stricter laws are necessary for ecological sustainability.

3. Bureaucratic Politics

The bureaucracy plays a central role in drafting and implementing policies. However, bureaucratic inertia, red tape, and turf wars between departments can delay or distort policy outcomes. Often, bureaucratic interests diverge from public needs, leading to incremental rather than transformative changes.

4. Coalition Governments and Political Fragmentation

In multiparty democracies, coalition governments are common. Policy decisions must accommodate diverse party agendas, which often results in compromise and diluted policies. Political fragmentation can slow down reforms and create policy paralysis, as seen in debates over land acquisition or labor reforms in India.

5. Ideological and Partisan Divides

Policies are shaped by ideological orientations of ruling parties. Left-leaning governments may emphasize welfare programs, while right-leaning ones focus on market liberalization. This ideological divide can lead to policy reversals whenever a new party comes to power, undermining policy continuity and stability.

6. Public Opinion and Media Influence

Public opinion, amplified by media and social networks, shapes the political feasibility of policies. Even well-designed but unpopular policies—such as fuel price hikes or pension reforms—may be abandoned due to public backlash. Politicians often prioritize policies that resonate with mass sentiment, even at the cost of economic rationality.

7. Corruption and Clientelism

Corruption diverts resources from intended beneficiaries and weakens public trust. Clientelism—where political support is exchanged for material benefits—distorts policy priorities, leading to inefficient allocation of resources. For instance, public funds may be diverted to projects that benefit select constituencies rather than society as a whole.

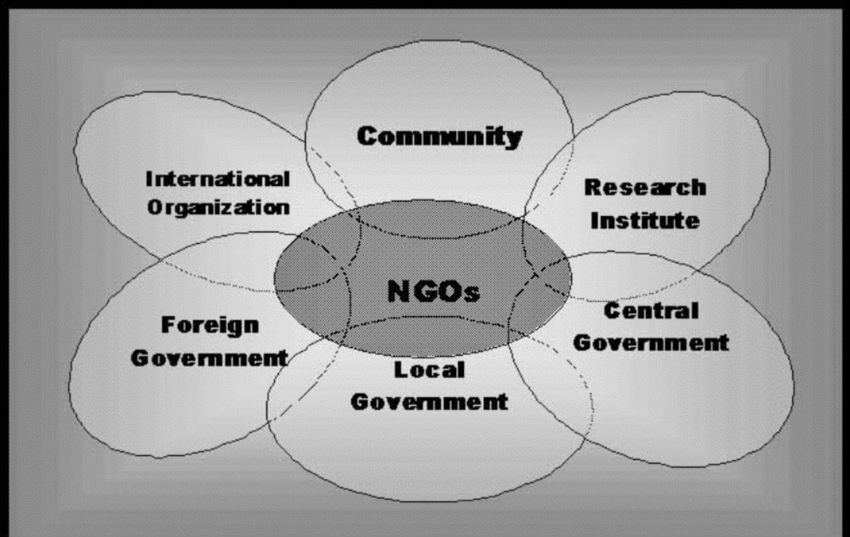

8. International Political Pressures

In a globalized world, national policies are influenced by international politics. Commitments under treaties (such as climate agreements) or pressures from global institutions (like the WTO or IMF) constrain domestic policy choices. Developing countries, in particular, may face limited autonomy in designing trade, fiscal, or environmental policies.

Economic Constraints on Policy Making

1. Scarcity of Resources

Governments face the fundamental constraint of limited resources. Financial, natural, and human resources are finite, and competing demands must be prioritized. Scarcity forces difficult trade-offs: more spending on defense may mean less for health or education.

2. Fiscal Deficits and Debt Burden

High fiscal deficits limit a government’s ability to launch new programs or expand existing ones. Similarly, a heavy debt burden constrains policy choices because significant revenues go toward debt servicing. This leaves limited fiscal space for welfare or developmental policies.

3. Inflation and Price Stability

Economic policies must consider inflationary pressures. Excessive government spending or subsidies can fuel inflation, reducing the purchasing power of citizens. Policymakers must balance growth-promoting expenditure with the need to maintain price stability.

4. Dependence on Foreign Aid and Investment

Developing countries often depend on external aid, loans, or foreign direct investment (FDI). Such dependence limits policy autonomy because donors and investors may attach conditions. For example, structural adjustment programs by the IMF in the 1980s required recipient countries to implement austerity and liberalization measures.

5. Global Economic Pressures

Globalization ties national economies to global markets. Economic crises, fluctuating oil prices, or recessions in major economies influence domestic policy space. For instance, during global recessions, governments may be forced to adopt austerity measures despite local needs for expansionary policies.

6. Regional Inequalities and Poverty

Persistent economic inequalities across regions and social groups constrain policy making. Governments must balance demands for equitable development with pressures for efficiency. Policies that benefit one group may be seen as discriminatory by others, complicating the design of inclusive programs.

7. Unemployment and Labor Market Constraints

High unemployment creates pressure for job-creation policies, often through public works or subsidies. However, these may not be sustainable in the long term. Similarly, rigid labor markets or resistance to reforms from trade unions constrain structural changes in labor policies.

8. Technological and Infrastructure Gaps

Economic constraints also arise from underdeveloped infrastructure, low productivity, and limited technological innovation. Policies promoting industrialization or digitalization may face hurdles if the economy lacks necessary foundations such as reliable power supply, skilled workforce, or digital access.

Interplay Between Political and Economic Constraints

Political and economic constraints are deeply interconnected:

- Populist Policies vs. Fiscal Prudence: Electoral pressures often push governments to introduce subsidies or loan waivers, even when the fiscal situation is unsustainable.

- Lobbying and Resource Allocation: Economic elites may influence political leaders to direct resources toward their interests, sidelining public welfare.

- Globalization and Sovereignty: International economic integration reduces national policy autonomy, but political leaders must still justify such constraints to their domestic constituencies.

- Reforms and Public Resistance: Economically necessary reforms (like labor or pension reforms) may be politically unpopular, leading to delays or dilution.

Thus, effective policy making requires balancing political feasibility with economic rationality.

Addressing Political and Economic Constraints

- Institutional Strengthening

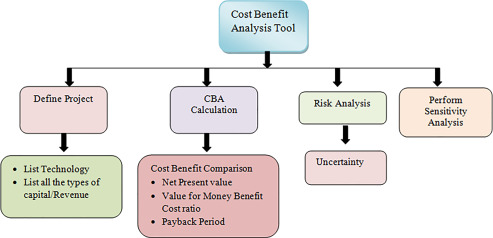

Independent institutions such as election commissions, anti-corruption bodies, and public audit agencies can reduce political manipulation and enhance accountability. - Evidence-Based Policy Making

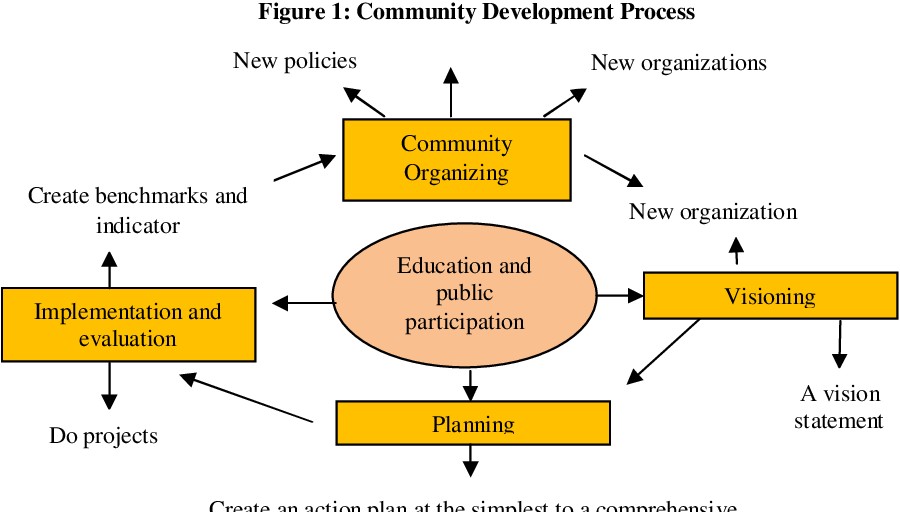

Using scientific research, data analytics, and expert advice can counter populism and lobby-driven policies. Transparent communication of evidence helps gain public trust. - Inclusive Governance

Ensuring participation of marginalized groups, civil society, and local communities in policy processes enhances legitimacy and reduces inequality. - Fiscal Discipline with Innovation

Adopting sound fiscal policies while exploring innovative financing (public-private partnerships, green bonds) can ease resource constraints. - Policy Continuity

Bipartisan consensus on critical reforms (such as health, education, or climate policies) reduces policy reversals across electoral cycles. - Global Cooperation

Active participation in international organizations and multilateral forums ensures that external pressures are negotiated collectively rather than imposed unilaterally.

Conclusion

Policy making is inherently a complex process shaped by political dynamics and economic realities. Political constraints—such as electoral pressures, lobbying, and ideological divides—limit rational, long-term decision-making. Economic constraints—such as resource scarcity, fiscal deficits, and global market pressures—restrict what is practically feasible.

Yet, these constraints need not paralyze governance. With institutional reforms, transparent communication, fiscal innovation, and inclusive approaches, governments can design policies that balance political feasibility with economic rationality. Ultimately, the art of policy making lies in navigating these constraints to achieve sustainable and equitable development.

You must be logged in to post a comment.