BY DAKSHITA NAITHANI

INTRODUCTION

After moving to internal organs such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow, a parasite causes illness. If not treated, it nearly invariably leads to death.

People get this condition by sandfly bites, which contracted the parasite after consuming the blood of a parasite-infected person. There are more than 20 distinct Leishmania parasites that cause the illness around the globe, and 90 different sandfly species that carry the infection.

However, in India, there is just one parasitic species, Leishmania donovani, and only one sandfly species, Phlebotomus argentipes, that spreads the illness.

Visceral leishmaniasis, commonly known as kala-azar, is marked by recurrent bouts of fever, significant weight loss, spleen and liver enlargement, and anaemia (which may be serious).

In underdeveloped nations, if the illness is not treated, the mortality rate can reach 100% in as little as two years.

SYMPTOMS

When people develop visceral leishmaniasis, the most typical symptoms are

FEVER

ENLARGEMENT OF SPLEEN AND LIVER

Misdiagnosis is critical, because kala-azar has a near-100 percent death rate if not treated properly. It does not always leave its hosts unmarked, even after restoration. A secondary form of the illness called post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, or PKDL, may develop after effective treatment—usually a few months after kala-azar, but as long as many years with the Indian strain. This illness begins with tiny, measles-like skin lesions on the face that grow in size and spread throughout the body.

In individuals who have recovered from the illness , it is characterised by a hypopigmented macular, maculopapular, and nodular rash and generally emerges 6 months to a year or more after the disease appears to be cured, although it can happen sooner or even simultaneously.

It is thought to have a crucial role in the disease’s maintenance and transmission, notably by functioning as a parasite reservoir. The lesions may eventually consolidate into disfiguring, bloated formations that resemble leprosy, causing blindness in certain cases if they extend to the eyes.

The visceral type of Leishmania is caused by two different species of Leishmania. L. donovani is the species found in East Africa and the Indian subcontinent, whereas L. infantum, also known as L. chagasi, is found in Europe, North Africa, and Latin America.

LIFE CYCLE

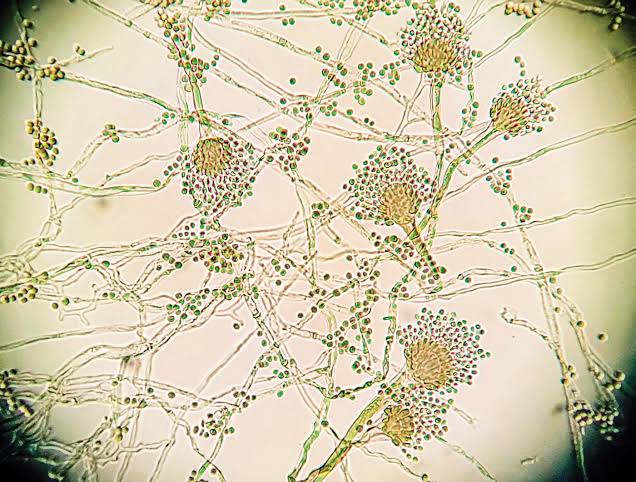

Life cycle is completed in two hosts: humans and sandflies. The adult female sandfly feeds at night and is a bloodsucker. When a Leishmania-infected person is bitten by a fly, the parasite is consumed along with the blood.

The protozoan is an amastigote, which is spherical, non-motile, and just 3–7 micrometres in diameter. The amastigotes inside the sandfly’s stomach soon change into the promastigotes, which are elongated and motile forms. It is spindle-shaped and thrice the size of the amastigote, and has a single flagellum that allows it to move. They live extra cellularly in the alimentary canal reproducing asexually and migrating to the proximal end of the gut where they become ready for a transmission.

The promastigotes are introduced after being released locally at the biting site as the fly bites. Promastigotes infect macrophages once inside the human host. They revert to their tiny amastigote form inside the cells.

In macrophage cells, amastigotes reproduce. They tear down their host cell by sheer mass pressure after repeated replication, although there is also new hypothesis that they are able to exit the cell via activating the macrophage’s exocytosis response.

The protozoans in the daughter cells then move to new hosts in fresh cells or through the circulation. The infection progresses and affects the spleen and liver in particular. Sandflies eat the liberated amastigotes in peripheral tissues, which starts a new phase.

TREATMENT

The traditional treatment is with

- Sodium stibogluconate

- Meglumine antimoniate

Resilience is increasingly prevalent in India, with resistance rates as high as 60% in some regions of Bihar. Amphotericin B in its many liposomal formulations is now the treatment of choice for visceral leishmaniasis acquired in India. The first oral therapy for this illness was miltefosine. Miltefosine had a cure rate of 95% in Phase III clinical studies.

The medicine is typically well tolerated compared to other medications. Gastrointestinal disruption on the first or second day of therapy (a 28-day course of treatment) is the most common adverse effect, but it has no influence on effectiveness. Miltefosine is a medication of choice since it is accessible as an oral formulation, which eliminates the cost and inconvenience of hospitalisation and allows for outpatient delivery of the drug.

The drawbacks include that after a decade of usage, there is evidence of decreased effectiveness. It is teratogenic and should not be used by women who are planning to have children. Sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) and meglumine antimoniate have been used to treat kala-azar (Glucantime). Only injections can be used to deliver these medications. They are poisonous, have several adverse effects, and are administered over a 30-day period.

You must be logged in to post a comment.