BY DAKSHITA NAITHANI

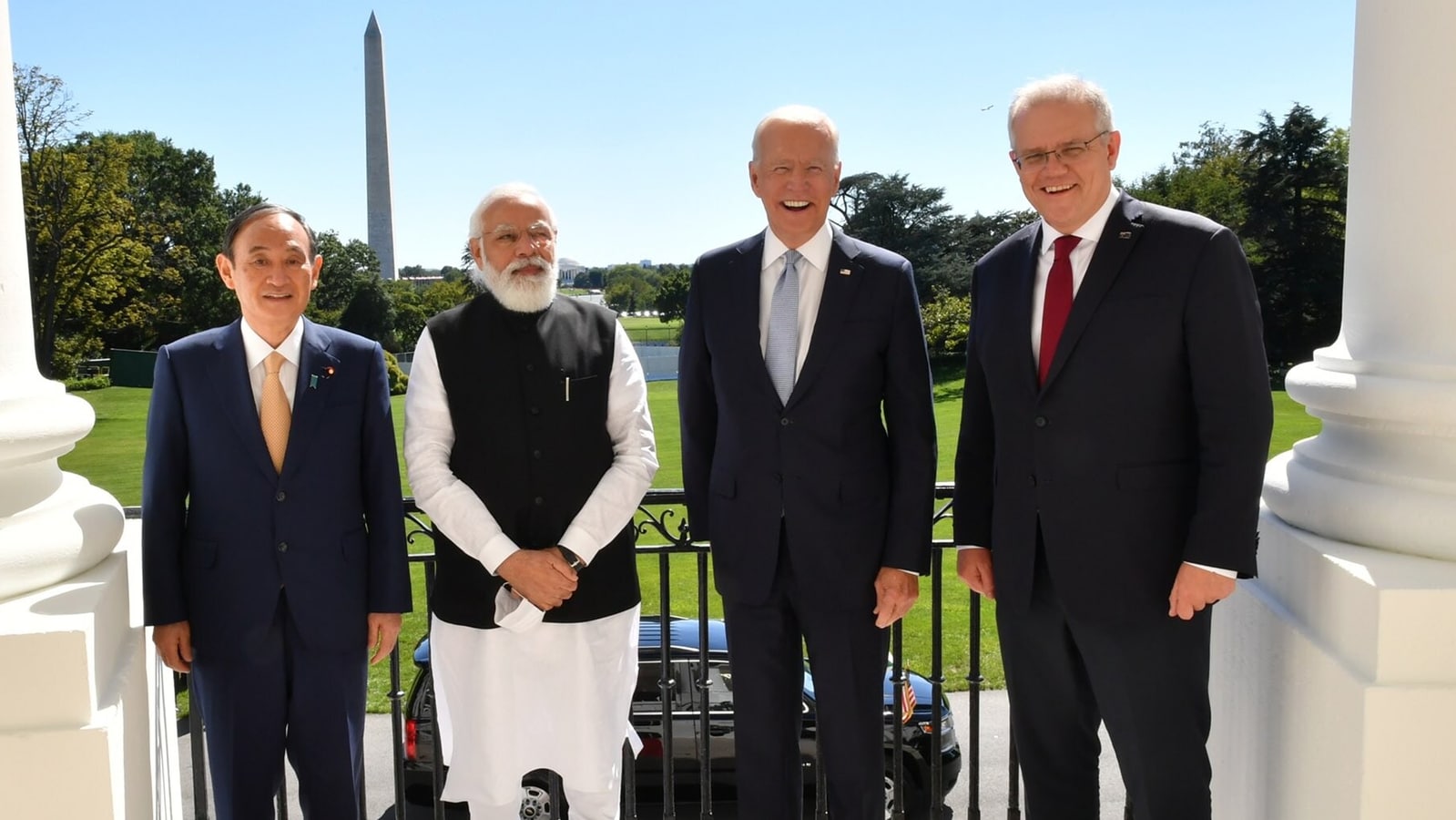

The Quadrilateral Dialogue was established in 2007 when four countries—the United States, India, Japan, and Australia—joined forces. However, it did not take off at first due to a variety of factors, and it was resurrected in 2017 after almost a decade due to factors such as growing country convergence, the expanding importance of the Indo-Pacific area, and rising threat sentiments toward China, among others.

Since then it has evolved into a platform for diplomatic discussion and coordination among participating countries, who meet on a regular basis at the working- and ministerial levels to discuss shared interests like ensuring a rules-based international order.

SIGNIFICANCE FOR INDIA

The Quad, ASEAN, and the Western Indian Ocean are the three groupings in which India participates as a partner in the Indo-Pacific area.

India as a Net Security provider

In the region of Indian Ocean India must be a Net Security Provider. Its supremacy in the IOR must be maintained and sustained if it is to claim this position as a Region. QUAD offers India with a platform to strengthen regional security through collaboration while also emphasising that the Indo-Pacific concept stands for a free, open, and inclusive area.( Inclusive here refers to a geographical notion that encompasses all countries inside it as well as those having a stake outside of it)

Countering China

The Quad offers India with a forum to seek collaboration with like-minded countries on a variety of problems, including maintaining territorial integrity and sovereignty, as well as peaceful dispute settlement. It also shows a united front against China’s unceremonious and aggressive actions towards the nation which is especially important now, since ties between India and China have deteriorated as a result of border intrusions along the Tibet-India boundary in many locations. The Chinese policy of encircling India with the String of Pearls poses a direct threat to India’s maritime sovereignty, which must be addressed.

Framing post-COVID-19 international order

QUAD can assist India in not just recovering from the pandemic’s impacts through a series of integrated measures, but also in securing a part in the modern international order. Enhancing such cooperation was one of the first actions made in 2021. The vaccination initiative will serve as a good litmus test for the QUAD administrations’ ability to work together.

Convergence on other issues

On a range of topics, India shares common interests with other Quad members, including connectivity and infrastructure development, security, especially counter-terrorism; cyber and maritime security; multilateral institutions reform, and so on. Assistance from members on these problems might help India achieve its strategic and economic objectives.

Supplementing India’s defence capabilities

Assistance in the sphere of defence among Quad countries, such as joint patrols, strategic information exchange, and so on, can help India overcome its disadvantages in terms of naval capabilities, military reconnaissance, technology, and surveillance systems.

Ensuring a free Indo Pacific

The Indo-Pacific region must be accessible and vibrant, regulated by international norms and bedrock values such as freedom of navigation and peaceful resolution of conflicts, and the nations involved must have the right to make decisions, free of coercion.

Counter-terrorism Table top Exercise for QUAD nations to improve collaboration and common capabilities in dealing with potential terrorist threats, as well as examine CT response systems.

INDIA’S ROLE IN THE INDO-PACIFIC

In the Indo-Pacific, India’s geographic and geopolitical importance provides a counterbalance to China’s rising influence in the Indian Ocean. India’s security concerns, centred primarily on China’s encirclement policy through port facilities in India’s neighbourhood mainly Gwadar and Hambantota and the desire to maintain and protect open and free sea lanes of information exchange against concerns about China’s chokepoint in the South China Sea and increasing maritime presence in the ocean

India’s critical significance in the Indo-Pacific may be seen as a multiple framework. First, unlike the Asia-Pacific architecture, the Indo-Pacific architecture allows New Delhi to move above its long-held standing as a middle-power. This is bolstered by India’s admission to the League of big powers especially the United States and Japan and the development of tight strategic ties with Washington and its regional allies. This promotes India’s great-power ambitions and force projection capability inside the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

Second, India’s Act East Policy and Extended Neighbourhood Policy benefit from New Delhi’s strong participation in the Indo-Pacific. New Delhi’s stronger relations with ASEAN members have also bolstered this boost.

Third, the development of India-US strategic relations, particularly in military, works as a significant counterweight to India’s adversaries. Increased engagements between New Delhi and Washington are exemplified by the four foundational contracts signed between the two countries, which include the General Security of Military Information Agreement, Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement, Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement, and Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement—all of which promote in-depth partnership Most significantly, the improved partnership boosts India’s military capacity, particularly when it comes to striking targets with precise accuracy.

Fourth, under India-Australia ties, which were elevated to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2020, India’s strategic position is bolstered yet further. In fact, Canberra and New Delhi inked nine agreements, the most important of which are the Australia-India Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement and the Defence Science and Technology Implementing Arrangement, both of which provide a framework for the two nations’ security cooperation.

Fifth, and most significantly, during COVID-19, India demonstrated its ability to be a first responder to a regional disaster by giving medical assistance to its near neighbours, including the Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Seychelles. In addition, India sent medical quick response teams to Comoros and Kuwait to help them prepare for the epidemic. In addition, nine Maldivians were evacuated from Wuhan, China, the site of the pandemic.

In addition, India pushed for virtual summits like the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation web conference on March 2020 and the “Extraordinary Digital G20 Leaders’ Summit” to help develop a worldwide reaction to the epidemic on 26 March 2020. In addition, New Delhi established a SAARC Emergency Response Fund for Coronavirus, with India contributing an initial 10 million USD.

In addition, as countries attempt to move manufacturing away from China, India is viewed as one of the world’s new “favoured” investment destinations. The enormous scale of India’s marketplace as well as the low labour costs, make it a desirable destination. Apple, for example, created a production facility in India in partnership with Foxconn, while Samsung, of South Korea, ceased operations in China and moved manufacturing units to India.

There is little dispute about India’s rising position in the Indo-Pacific, not just as a significant participant but also as a responsible actor. As a result, India’s manoeuvring room in the post-COVID international order is anticipated to expand, as India is seen as one of the major movers in guiding policy and protecting allied interests in the Indo-Pacific. COVID-19 has, in fact, expanded the Quad framework, allowing important parties to play a more active role in addressing critical conventional and unconventional regional issues.

You must be logged in to post a comment.