By Shashikant Nishant Sharma

Traffic signal coordination is a critical aspect of urban traffic management, aimed at optimizing the flow of vehicles and reducing congestion at intersections. By synchronizing traffic signals, cities can improve the efficiency of road networks, enhance safety, and minimize delays for drivers and pedestrians. This article explores the principles of traffic signal coordination, its benefits, the technologies involved, and best practices for effective implementation.

Principles of Traffic Signal Coordination

Traffic signal coordination involves the strategic timing of traffic lights to ensure smooth vehicle flow and reduce stoppage time. The key principles include:

- Green Wave: This concept involves synchronizing traffic signals along a corridor so that vehicles traveling at a certain speed experience a series of green lights, minimizing stops and starts. The goal is to create a “green wave” that allows vehicles to move smoothly through a series of intersections.

- Cycle Time: Each traffic signal operates on a cycle that includes green, yellow, and red phases. Coordination involves optimizing the length of these cycles to balance the needs of different traffic movements and reduce overall delay.

- Phase Timing: Coordinating the duration of green, yellow, and red phases to align with traffic demands. This involves adjusting signal phases to accommodate peak traffic periods and minimize delays.

- Coordination Across Intersections: Effective coordination requires managing multiple intersections along a corridor to ensure that traffic flows smoothly without unnecessary stops. This involves considering the traffic patterns, volume, and intersection layout.

Benefits of Traffic Signal Coordination

- Reduced Congestion: By synchronizing traffic signals, vehicles can travel more efficiently through intersections, reducing the likelihood of traffic jams and congestion. This can lead to smoother traffic flow along major corridors and decrease overall travel time.

- Decreased Emissions: Reduced idling time at traffic signals lowers vehicle emissions, contributing to better air quality. Fewer stops and starts mean less fuel consumption and lower greenhouse gas emissions.

- Improved Safety: Coordinated signals can reduce the number of accidents caused by sudden stops or conflicting traffic movements. Predictable traffic flow and fewer red-light violations contribute to enhanced safety at intersections.

- Increased Efficiency: Efficient traffic signal coordination improves the overall efficiency of the road network. This benefits not only private vehicles but also public transportation systems, emergency vehicles, and freight movements.

- Enhanced Pedestrian Experience: Coordination can also improve pedestrian safety by ensuring adequate crossing times and reducing the frequency of conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles.

Technologies for Traffic Signal Coordination

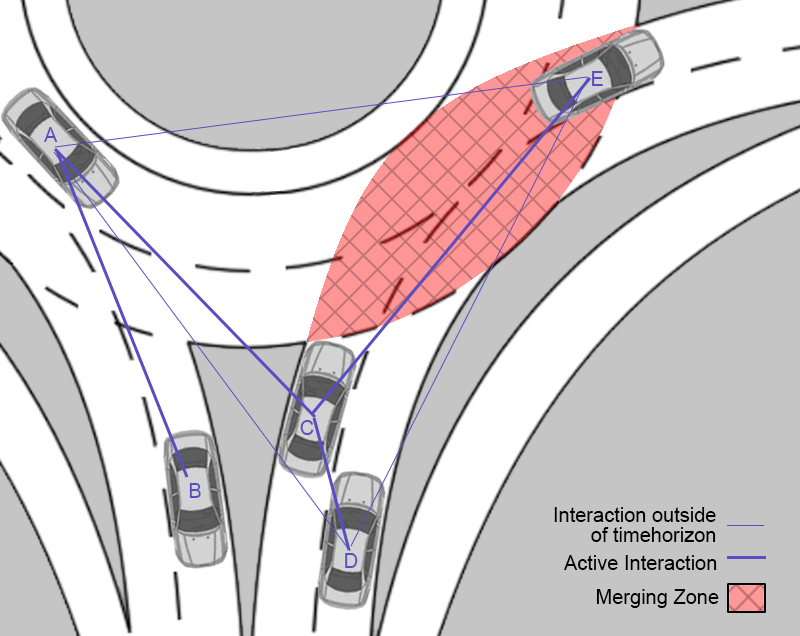

- Adaptive Signal Control Systems (ASCS): These systems adjust traffic signal timing in real-time based on current traffic conditions. They use sensors, cameras, and data analytics to optimize signal phases and adapt to changing traffic volumes.

- Traffic Management Centers (TMCs): TMCs centralize traffic data collection and control. They use advanced software to monitor traffic conditions, manage signal timings, and coordinate signals across multiple intersections.

- Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) Communication: This technology allows vehicles to communicate with traffic signals, providing real-time information on signal status and optimizing traffic flow based on vehicle positions.

- Signal Preemption and Priority Systems: These systems allow for priority signaling for emergency vehicles and public transportation, ensuring that they can navigate through intersections more efficiently without disrupting overall traffic flow.

- Traffic Flow Modeling Software: Modeling software simulates traffic flow and evaluates the impact of different signal timings and coordination strategies. It helps planners and engineers design effective coordination schemes and predict their outcomes.

Best Practices for Traffic Signal Coordination

- Data Collection and Analysis: Collecting accurate traffic data is crucial for effective signal coordination. This includes traffic volume, flow patterns, and peak hours. Analyzing this data helps in designing optimal signal timings and coordination strategies.

- Public Involvement: Engaging with the public and stakeholders is important for understanding local traffic patterns and concerns. Public feedback can help in refining signal coordination strategies to better meet community needs.

- Phased Implementation: Implementing traffic signal coordination in phases allows for testing and adjusting strategies before full-scale deployment. This approach helps in identifying issues and making necessary adjustments.

- Continuous Monitoring and Adjustment: Traffic conditions are dynamic, so ongoing monitoring and adjustments are essential. Regularly reviewing signal performance and making data-driven adjustments ensures that coordination remains effective.

- Integration with Other Traffic Management Strategies: Coordinated signals should be integrated with other traffic management strategies, such as congestion pricing, traffic flow optimization, and public transportation improvements. This holistic approach enhances overall traffic management.

- Training and Capacity Building: Ensuring that traffic management personnel are trained in the latest technologies and best practices is crucial for effective signal coordination. Investing in professional development helps maintain high standards in traffic management.

Case Studies

- Los Angeles, California: Los Angeles has implemented the Advanced Traffic Signal Control (ATSC) system to manage its extensive road network. The system uses real-time traffic data to adjust signal timings and reduce congestion along major corridors.

- Singapore: Singapore’s Integrated Traffic Management System includes adaptive signal control and real-time traffic monitoring. The system adjusts signal timings based on traffic conditions and integrates with other traffic management measures, such as congestion pricing.

- London, United Kingdom: London’s UTC (Urban Traffic Control) system coordinates traffic signals across the city, optimizing traffic flow and reducing delays. The system uses data from sensors and cameras to adjust signal timings and manage traffic congestion.

Challenges and Considerations

- Complexity of Implementation: Coordinating signals across multiple intersections and corridors can be complex, requiring sophisticated technology and detailed planning.

- Cost: Implementing and maintaining advanced signal control systems can be costly. Budget constraints may limit the scope of coordination efforts.

- Technological Integration: Integrating new technologies with existing traffic management infrastructure can be challenging. Ensuring compatibility and seamless operation is essential for success.

- Public Acceptance: Changes to traffic signal timings can impact drivers and pedestrians. Clear communication and public outreach are important for gaining acceptance and understanding of the benefits.

Conclusion

Traffic signal coordination is a powerful tool for improving traffic flow, reducing congestion, and enhancing overall road network efficiency. By employing advanced technologies, following best practices, and addressing challenges, cities can create more effective and sustainable traffic management systems. The benefits of well-coordinated traffic signals extend beyond reducing travel time and emissions; they contribute to safer, more livable urban environments. As urban areas continue to grow, investing in and optimizing traffic signal coordination will play a crucial role in managing the complexities of modern transportation systems.

References

Bazzan, A. L. (2005). A distributed approach for coordination of traffic signal agents. Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, 10, 131-164.

Dehalwar, K., & Sharma, S. N. (2023). Fundamentals of Area Appreciation and Space Perceptions.

He, Q., Head, K. L., & Ding, J. (2014). Multi-modal traffic signal control with priority, signal actuation and coordination. Transportation research part C: emerging technologies, 46, 65-82.

Kang, W., Xiong, G., Lv, Y., Dong, X., Zhu, F., & Kong, Q. (2014, October). Traffic signal coordination for emergency vehicles. In 17th international IEEE conference on intelligent transportation systems (itsc) (pp. 157-161). IEEE.

Kushwah, N., Natariy, R., & Jaiswal, A. (2015). Traffic signal coordination for effective flow of traffic: a review. Int J Sci Res Dev, 3, 1803-1806.

Lodhi, A. S., Jaiswal, A., & Sharma, S. N. (2023). An Investigation into the Recent Developments in Intelligent Transport System. In Proceedings of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies (Vol. 14).

Xiang, J., & Chen, Z. (2016). An adaptive traffic signal coordination optimization method based on vehicle-to-infrastructure communication. Cluster Computing, 19(3), 1503-1514.

Sharma, S. N., & Abhishek, K. (2015). Planning Issue in Roorkee Town. Journal for Studies in Planning and Management.

You must be logged in to post a comment.